This is the last of three installments recounting Khvostov’s and Davydov’s winter on Kodiak Island.

The previous installment:

Davydov makes several visits to a place he calls Rubtsov, which means scars, on Afognak Island, northeast of Kodiak. This is an odinochka, a one-person post: odin is the number one in Russian. Rubtsov was apparently near the site of the historic village of Afognak. The Alutiiq people of the region also remember a place at that village called Naschkuchalik, which, if it is a Russian name, as it seems to be, means something like Our Little Pile. Afognak was, among other things, the local hub for production of yukola, the salmon dried for year-round use from the catch from the annual seasonal run.

Toward the end of the episode, Davydov is clearly just killing time, waiting for Baranov to finish his correspondence. They finally board their ship and weigh for Okhotsk, but a calm forces them to come to anchor again and wait for Chapter V to sail away from Kodiak.

Remember that “American” here means Alaskan Native. As a reminder, too, we’ll again encounter old Russian measures: sazhen, often translated as fathom, but around 7 feet, arshin, which is about 28 inches, and verst, which is about a kilometer (0.6 mile). And, of course, a baidarka (the word more or less means “little canoe”) is a kayak – aside from the materials and size (the Alaskan baidarkas were pretty big), your mental picture of a kayak will serve nicely. The promyshlenniks were the Russian fur trappers. Another word with which I’ve had some trouble is Kayuri, who were Alaskan natives employed by the Russian-American Company. The term now refers to drivers of reindeer or dogsleds (I suppose Santa Claus is one), and I’ve occasionally translated it as Mushers, but here I just stick with Kayuri.

DAVYDOV’S NARRATIVE (Continued)

CHAPTER IV (Concluded).

8 April [1803].

An American who arrived yesterday from the south side of Kodiak said that on the high, detached rocks at Chiniak cape there are sea lions, usually called sivuchami or siuchami. These beasts have not appeared near the harbor for five years. Out of curiosity, I went to see them, taking a stryeltsa with me (that's what the archers are called here). The wind was blowing fresh from the SW, and a rather large swell remained from the previous weather; so we rowed along the coast, around the entire Chiniak Bay. Archer Brusenin, on the way, shot two seals [not sea lions –JT.], while I shot nine ducks and several black sandpipers; but we did not find sea lions at the cape, and went back straight across the bay, for the wind had died down. Approaching the islets near the harbor, I took off the sprayskirt from my hatch and rowed calmly; and suddenly hearing Brusenin shouting something in the Konyak language and seeing that the rowers at the same time began to row with all their might, I looked back and saw a steep high roller coming towards us, from which, however, we escaped. Soon after that I encountered another one of the same kind, and as I did not have time to fit my sprayskirt completely tightly, some water got into the baidarka. Such turbulence happens over the underwater rocks, here called Potainiks (Secrets). Near the Potainiks it is calm most of the time, but sometimes a huge swell of water suddenly rises, extremely dangerous for baidarkas. This action they describe by saying: the potainik plays. The Russians and Americans assure us that some of these secret places play once, others twice a day, some once a month, and others once a year, and always at a certain time. In high winds, great waves always go over them. Baidarkas sometimes sink, accidentally hitting the hidden hazard, which at that time begins to play. The Americans know most of them and try to go around them even in calm weather. Not all hazards produce such an action as I have described, for which reason I should think that what are called secret hiding places contain something special, like funnels, or something else.

10 April.

This day was marked by a strange adventure: a ninety-six-year-old promyshlennik wanted to marry an unattractive forty-five year old American woman, who did not agree for a long time, but finally gave him her word; but in the church she said that she did not want to marry him, so the wedding broke up, and the old man was extremely upset.

In the evening, a party of Alaskan baidarkas arrived here, setting off along the coast of America [I read this as meaning the Alaskan mainland –JT.] to hunt for sea otters. A promyshlennik who arrived with them brought by deception one Alaskan, who killed a Russian promyshlennik but spread the story that he died from a boil, which the other Americans in that place willingly confirmed. The murderer was a fine young man who had formerly been one of the Amanats [hostages] in the harbor and fell in love with the wife of this promyshlennik, a native of Kodiak. They asked, why did you kill the Russian? The girl told me to do it, he said. What must be done to you for that? The same, to kill me, he answered boldly. However, he and his co-conspirators were only flogged with a rope’s end, and then they wanted to send him to Yakutsk with the Kayuri on the first ship.

That very day, from Chugach Bay [on the Kenai Peninsula, northeast of Kodiak], we received news that on the island of Tsukli the side of a ship washed ashore, four sazhens [almost 30 feet] in length; and from Ukamok [the native name of Chirikov Island, southwest of Kodiak] they brought a box thrown from the sea with blue cloth and a grass hat, which are usually worn on the Sandwich Islands. These last were washed up in the autumn, and therefore it must be concluded that some English or United States ship wrecked about that time.

This winter, they also brought from Sitkinak Island [off the southern end of Kodiak] a castaway stub of a large wax candle, which could only have been from a Russian ship, and probably from the company’s ship called Phoenix. This vessel of the Russian American Company, built in America, was to carry the Archimandrite from Kodiak, for his consecration as Bishop in Irkutsk. On the Phoenix, they built a shelter for the privacy of the Archimandrite, but only attached it at the bottom. Some itinerant Englishman was made the captain of the ship; and this title, even in America, is sometimes enough to inspire a high opinion of a man’s seamanship. The Phoenix set sail from Okhotsk in the month of August with the Bishop, with all his train, and with eighty or more promyshlenniks, among whom yellow fever still raged in Okhotsk. Three masts were raised on the ship (although it was a vessel of only 100 or 110 tons) just so the company could say it has a three-masted vessel, which are generally called frigates here. At the end of October, the Phoenix was sighted from Unimak Island; after that it left behind only fables and guesses about the place and cause of its shipwreck. But it is likely that the turbulent seas, the poorness of the ship, the illness of the people and the ignorance of the master were the reasons for the loss of the Phoenix. It was costly to the company, both in terms of cargo and in the number of people whose failure to reach America weakened the company’s establishments and trade. The cargo of this ship is scattered across the great expanse of America: they have found flasks of vodka, with spoiled wine, wax candles, a samovar, a steering wheel, upper beams and other things, starting from Unalaska, as far as Sitkinak and beyond.

19 April. [Davydov does not mention it, but this date marked one year since their departure from St. Petersburg. –JT.]

By evening, a party from the south side of Kodiak, more than 200 baidarkas, gathered in the harbor; the Konyags from the northern side never enter it, but having stocked up on yukola [dried salmon] on Karluk, they go straight to the island of Shuekha. There or a little farther along, having joined with another party and having waited for the Russians to be sent to supervise the trapping, they all go together.

Today the ninety-six-year-old man, whom I mentioned above, again proposed to his beloved, and she married him.

20 April.

Around noon, the party began to leave the harbor.

A one-seat baidarka on display at Fort Ross, on the Sonoma Coast. The craft is about 18 feet long.

23 April.

In the morning I set off with some of the Russians to the island of Afognak, where in the main company live eight or ten promyshlenniks and many Kayuri. Only here do they store halibut yukola. From here, after parting with my fellow travelers, I went to the Rubtsov odinochka, located 16 versts away.

24 April.

A strong contrary wind forced me to stay the whole day at the Rubtsov odinochka. This is time the ducks fly away from here to look for places to lay their eggs, and the geese and swans begin to appear. In the bay, I shot three geese and several ducks.

25 April.

I went home after sunrise.

3 May.

The galliot Alexander Nevsky went to Yakutat. Another vessel, called the Olga, built on Kodiak from spruce, went to Unalashka. It is known that spruce lumber is very poorly suited for the hulling of ships: The Olga can serve as new proof of this. When Baranov went on it for the first time, he had to constantly bail out water, so that eventually they were pumping sea plants out of the pumps, and finally the ship sank in the shallows. But even after that, they put another sheathing on it, then a third, and they have not stopped sending it out to sea. This vessel never leaves the coast, but in a contrary wind stands somewhere at anchor. Meanwhile, as poor as it is, Baranov does not have a better ship.

12 May.

Today Khvostov and I, taking the archer with us, went to look at the sea lions, which again began to appear on the rocks at Cape Chiniak. We arrived there at high tide: the time was inconvenient for shooting because the breakers reaching the top of the rocks kept the animals from lying quietly on them. The weather was rainy. We landed at the Cape Chiniak, where we spent the night, Khvostov in a straw hut made by the islanders who were once there, and I in a tent, like the ones the local Americans usually make up of baidarkas and bedding during their long journeys. The baidarka is placed sideways on the windward side, then a small cover is made from the oars laid on it parallel to the ground. Under such a semi-closed tent I was fairly well protected from rain and wind. A sea lion barked all night long.

13 May.

At 10 o’clock in the morning, when the tide was at its lowest, we rowed up to the rocks. The archer came out on one empty cliff, and the sea lions lay on another, fifteen sazhens [about 25 yards] away from him. These animals see badly, but they have a very good sense of smell; for which reason they usually approach them from the leeward side, otherwise they will notice and throw themselves into the sea. While the archer was getting ready, we had time to examine these animals. Their skin color is light brown, and whiter on females. The head is short with barely noticeable ears. They bark incessantly, raising their snouts upward and turning their heads, as if sniffing something. Each animal showed several wounds, of course received during fights for females. The local sea lions do not have skin on their snouts, unlike, according to the description in the Anson voyage, the sea lions of the island of Juan Fernandez [off of Chile – Anson’s voyage was a century earlier! –JT.]. These animals, lying down, seem in a way to resemble lions; from which of course they got their name.

When we shot at the first sea lion, it fell into the water and sank, dead or alive is unknown, because these animals, when they are killed, do not remain on the surface of the water. At this shot one sea lion jumped into the sea, and the rest lay calm. With the second shot, one sea lion was killed, another, lying next to him, remained on the rock; the rest threw themselves into the sea. With the third shot, the one remaining was wounded, but jumped into the water. The surf all around the cape, and especially near the detached rocks, became very high due to the east wind. It was impossible to approach the rock in a single baidarka; for which reason we paired up, waited for a likely time, rowed up to the rock and deposited two Americans on it, who cut the sea lion’s throat. They blew air into it, tied it with a rope so that the wind would not escape, and pushed the beast, which no longer sank, into the sea. Then, picking up the Americans, we towed the sea lion to the shore, cut it into pieces, laid it in baidarkas and set off for the harbor. The weather was cloudy the whole time with rain, and on the way there was a fresh, contrary wind with a greater swell, on account of which we did not make it home quickly.

17 May.

After lunch, for an excursion, Khvostov and I rode in a three-opening baidarka to the forest island. Rolling away from it, we capsized, but after pouring out the water, and putting two more people instead of the load in the bottom of the baidarka, we continued on our way.

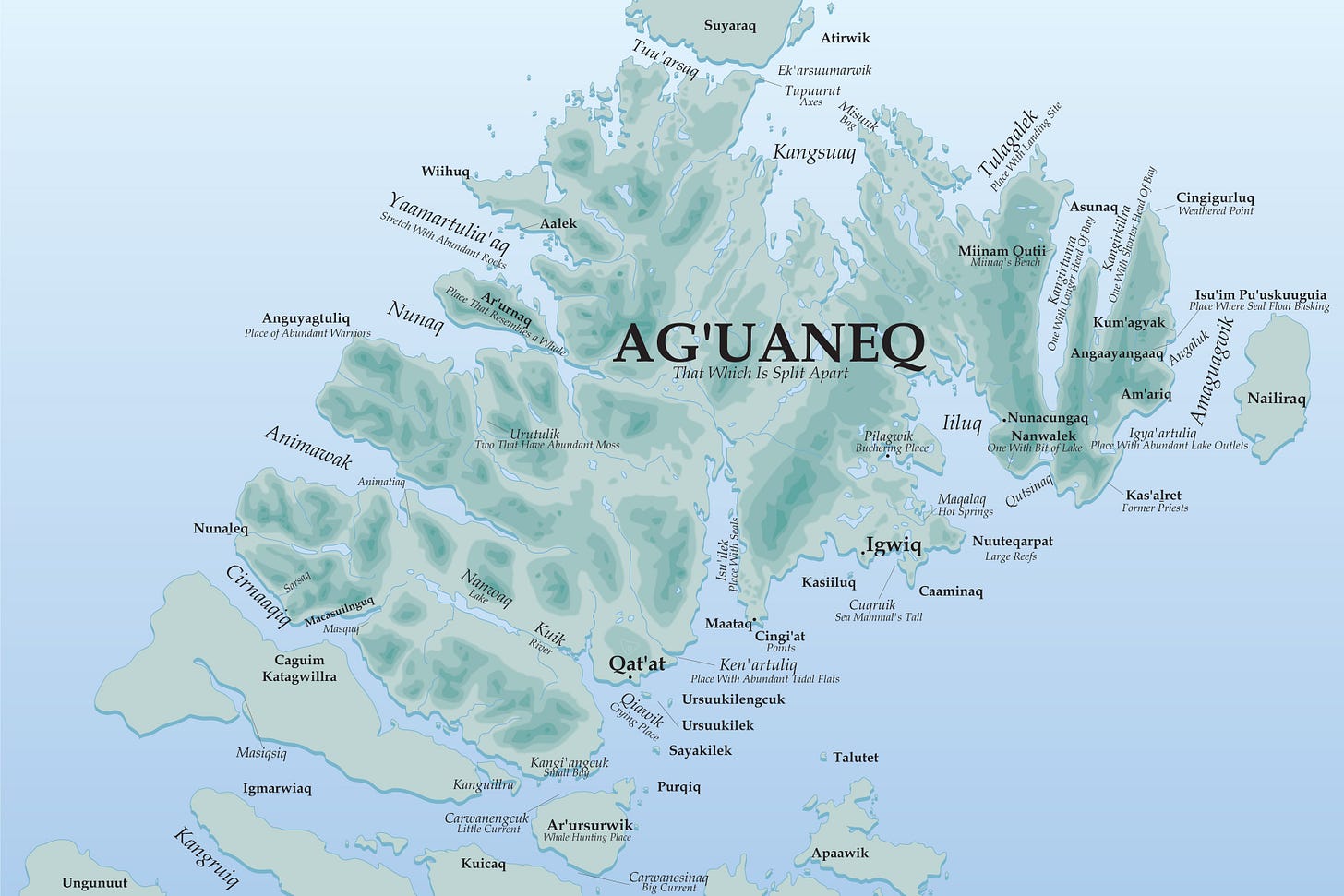

Afognak Island. Rubtsov was probably across the bay from Qat’at, on the southern part of the island. Afognak appears to be an attempt at the island’s Native name, Agʻuaneq. Source: https://afognak.org/data-recovery/afognak-placenames/

24 May.

Today, Trinity Day, we heard Mass in the morning; the evening we spent at Baranov’s: we sang, danced, were very merry, and dispersed at two o’clock in the morning.

30 May.

On this date the ship St. Ekaterina departed for Yakutsk.

13 June.

In the morning we, that is, Khvostov and I, went to Spruce Island, having learned that a whale had been beached there. This was a kind of minke whale, and no longer than four sazhens [less than 30 feet]. I will not dwell on the description of such a familiar animal. In our presence, they cut him into pieces, took half to the company, and gave the other to the promyshlennik who killed him, which was recognized by the stone arrow left in the whale with a sign carved on it. These marks are recorded in the Kodiak office, but the promyshlenniks know them among themselves anyway.

Not wanting to spend the night on a barren shore in such damp weather, we left the whale that night. The fog was so thick that at ten sazhens it was impossible to see anything; but the Americans, by their amazing cleverness in such cases, brought us directly to a hut, about twelve versts from the beached whale. Here we spent the night, and the next morning we arrived at the harbor.

17 June.

We were already quite ready to sail from Kodiak; but as Baranov had not yet completed all the papers required for sending to Russia, we waited for them without any other business. Today I went to the Rubtsov odinochka on Afognak. In the middle of the strait between Kodiak and Afognak, water appeared in the baidarka; but as there was nothing to do about it, we just tried to row harder. Arriving and pulling the baidarka ashore, we saw three holes at the bottom along the keel itself, one 2 1/2 quarter-arshins [maybe 17 inches], the other a quarter [7 inches], and the third two inches; plus two more small ones on the side. Everyone marveled that we didn’t drown because they guessed that the baidarka had been broken through while still in the harbor, where we sat down in the harbor and knocked oars. Only the mat usually placed inside the baidarka, and the bearskin on top of it, covered these holes; but if the sea had not been so calm, then of course the whole baidarka would have been ripped open.

18 June.

Here we picked wild onion to salt and stock up on it for the duration of the voyage to Okhotsk. It is known that wild onions, wild garlic, spoon grass, and some other plants are very useful to protect against scurvy disease. So, in order to pick up a fair amount of wild onions (it does not grow on Kodiak, at least near the harbor), we stayed all day at the Rubtsov odinochka, where at the present time they store fish, for which up to thirty women and Kayuri are gathered here for cleaning and drying. Yukola is hung in the same way here as in Okhotsk, only first, when the fish going to the rivers are very fat, the fat itself is cut off; for this does not have time to dry out along with the other parts, but only turns brown.

At this time, a great multitude of red fish ran in the river. Out of curiosity, I ordered a small seine cast in the morning, which pulled out more than two thousand fish at a time, although they threw many back, and turned the net and let all the fish out of it; for it is not possible to clean so many in a day or two, and on the third the fish will certainly spoil. Moreover, people are not able to pull the seine with such a quantity of fish to the shore without tearing it up.

19 June.

At 5am I set off for home.

25 June.

In the evening on this date, having received the rest of the papers from Baranov, we weighed anchor during the calm, and going with the help of a tow to the forested island, we again rested at anchor in a small sandy bay.

It took a few days for Davydov and Khvostov to find a favorable wind, but they finally managed to leave Kodiak and make their way back toward Okhotsk. In the next episode we’ll see that swashbuckling at sea doesn’t necessarily require swordplay, or even an enemy – just exceptional sailing skill.