This is the second of three installments, in which Khvostov and Davydov pass the winter on Kodiak Island. In this episode, Davydov describes his activities. Since he was a Naval officer, it’s no surprise that he spent much of his time on the water. Most of this installment describes a series of excursions he made in baidarkas, the kayaks of the Alaskan natives. If you’ve ever wondered what it would be like to kayak in the waters of the Gulf of Alaska in winter, Davydov’s account might give you an idea.

The previous installment:

Davydov makes a couple of references to a “forested island” just off Kodiak. Not far from the harbor where the Russian-American Company’s base was situated (on Chiniak Bay, near the current town of Kodiak), there is an island called Woody Island. It seems likely that is the island Davydov is describing. He also mentions Afognak, an island adjacent to and north of Kodiak.

At the end of this episode, Davydov makes reference to a Bystry Strait, so called because of the rapid current through it. The Russian word bystro means “quickly,” and the French word bistro, a restaurant whose menu features dishes designed for a fast final preparation before coming to table, is a direct borrowing from Russian. As a reminder, the promyshlenniks were the Russian fur-trappers, who worked for the Company, usually on multi-year passports.

DAVYDOV’S NARRATIVE (Continued)

CHAPTER IV (Cont’d).

30 December [1802].

The Toyon, or the chief, of the forest island, came to invite us to his play, to which we went after dinner. With great difficulty we climbed into Kazhim, or theater, whose top was rounded; inside it was clean and not stuffy. We were seated on a bearskin stretched out on a bench. In the middle of the Kazhim, a large bowl was burning, as were several small ones along the walls; in the place of performance, the ceiling above our heads was covered with dry grass. The performers represented hunters going to trap animals, that is, the same thing that we saw in the Kazhim at the harbor. And here, too, two people were sitting near the bowl with tambourines, two stood on either side of it with small oars and rattles, naked, with red stripes painted all over their bodies, wearing masks and holding sticks in their mouths. These masks are made of bent twigs, so that through them you can see almost the entire face of the person, painted with white and red dyes. Arrows, baidarkas, stuffed animals, and other devices hung over the bowl on crossbeams connected crosswise with a quadrangle, and one person swung all this, as before. But here, another person sat on a suspended plank at each of the four corners of these crossbeams. These wore the same masks as the first two, and had various stripes painted along their bodies. They also swayed. However, the performance was the same. The reason for this tradition, according to the Toyon’s account, was as follows: one islander hunted for five years without killing a single animal, although he was previously considered a glorious hunter. Then, out of sorrow, he left the people and lived in the mountains. One night, which he was spending at the top of a hill, he had a dream; and coming to the village after that, he put on this play, just as he saw in the dream. Since that time, his hunting was always met with the happiest success; so even now the islanders present this play, in the hope of having a successful hunt.

The spectators consisted of smartly dressed native inhabitants. The women were in their best dresses; like this: in cloth parkas, with collars of squirrel or cormorant. Almost all had bones threaded through the nasal cartilage, or wore beads strung on sticks on the hands, feet, neck and ears, as much as they could fit, or as much as they had. Everyone was very pleased with the performance. As the play went on, the women continually brought food, regaling everyone with it; but as they watched the play, the boys snatched the dishes out of their hands and ran away. The women chased after them and everyone laughed loudly.

At the end of the show, called by the Russians a playlet [the Russian word igrushka generally means toy, but I take it here as a diminutive of igra, or play – JT.], The Kasyat [the sage] came out and shouted something. The Toyon, due to his imperfect knowledge of the Russian language, could only say that it referred to three people who had arrived at this time. Then we went out, but hearing the sound of the tambourine, we returned to the kazhim, where we saw the four people jumping around the bowl, who had previously been sitting on the suspended planks. All this, it seems, was done just to keep the audience occupied while they prepared for another performance; since these people, having danced a little, threw off their masks and sat down with the others on the floor.

Soon after that, everyone sat down in their places, and the performance began: two began to beat the tambourines in time to the song that all the spectators were singing, and then a man appeared with a painted body, in a mask around which painted slats were glued in a semicircle, with eagle feathers completing its decoration. He went up with his back to the audience, stood on his knees turning away from them for a long time, shook his rattles quietly in rhythm and gradually turned, then suddenly jumped up, rattled louder and seemed to shake all over, constantly shifting his position. After dancing for half an hour, he went out, and in his place appeared two men in masks similar to the previous one, and between them a woman with a semicircle around her head. These also entered with their backs to the audience, stood on their knees, then stood up, turned to the audience and made different gestures, coordinating these very skillfully with the sound of rattles. In place of these, one man appeared in a costume with a semicircle around it and with rattles. He entered, like the previous ones, with his back to the audience, danced better, and the action ended.

I could not imagine the reason for this performance and did not expect such coordination in the movements and dancing of these untutored people. I also forgot to say that before the start of the last performance, the Kasyat came out and shouted something, then during the action he said in advance what they should sing and directed the choir.

My occupation and exercise were always the same, consisting of reading, walking along the shore with my gun, and visiting the natives in their homes. For this I took a small supply of food, got into a baidarka and left the harbor for five, six days or more. Now I will describe some of those travels.

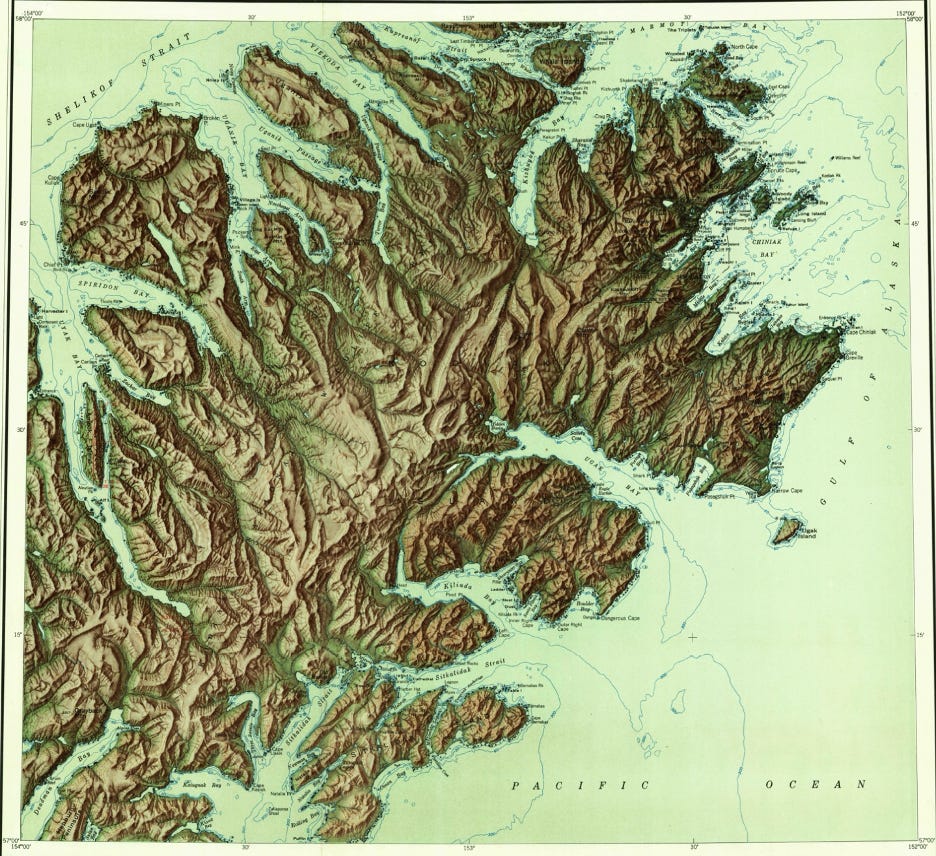

Modern map of Kodiak Island Borough, Alaska. The Company headquarters was near Kodiak, and most of Davydov’s excursions were to the north and west of there. Shelikof Strait is named for the founder of what eventually became the Russian-American Company. – Kodiak Island Borough GIS Mapping Center

15 January 1803.

I walked along the shore to shoot, and in the grove I met a bear. We parted company, however, without any misadventure to each other.

9 February.

I went in a boat to the forest island, and on the way I shot an eagle with a white tail, one duck and several sandpipers.

27 February.

I went in a three-person baidarka, taking with me three more of the same. At first, the weather was rather warm and clear, but at 5 o'clock a fresh contrary wind caught us in the middle of Kizhuyak bay [a bay on the north side of Kodiak Island –JT.], so in the evening we landed at the Kizhuyak village of the natives, or zhilu [this is a bit obscure, but it could be a derogatory reference to a tight-fistedness –JT.] , as the Russians usually call them, and I spent the night at the Toyon’s house.

28 February.

In the bitter cold the wind was so strong that I found myself forced to stay for several days with the natives. I spent the evenings and nights with them, and during the days I went to the interior.

1 March.

The weather was cold but calm. I set off. I traveled to many places where it was possible to shoot ducks and seals. In the evening we landed at a small bay, at which there was a grass hut for hunting seals. It was a square sazhen in size [about 7 feet square], but not more than one and a half arshins [about 3-1/2 feet] high. Soon there was a strong wind and a blizzard: we put grass in the hut, brought in hot stones, and thus spent the night very calmly and warmly.

2 March.

Severe frost and high surf in the strait between Kodiak and Afognak, left over from yesterday's storm, did not allow me to leave. I walked along the shore and shot partridges, and in the evening I caught ducks with a net.

3 March.

The cold snap continued and the fierce wind began again. I moved to a small island, where there are many partridges, but I could not shoot a single one: in winter they are completely white, so that it is very difficult to see them when they sit in the snow without moving.

4 March.

Cold, but calm weather. At three o'clock in the afternoon I arrived at the harbor. On the way, I shot more than a dozen ducks, but the thick snow that fell stopped me from shooting more.

6 March.

In the morning Khvostov and I set off to a high mountain located near the harbor itself. We had to rest several times on the way up. On the mountain we saw two foxes, one of which was black and brown, so large that we took it for a bear. From the top of this mountain you can see the entire Chiniak Bay with islands and rocks in the water, part of the forest island and Afognak, and then the vast sea; to the other side, many ridges of stone mountains. The expansive views always make a pleasant impression, and it was with great pleasure that I stood in one place for more than half an hour, admiring this majestic spectacle and surrendering to my delighted imagination. These pleasures are known more to people living alone, and it is hardly possible to describe them. A person becomes more satisfied with his existence when, standing on a high mountain and breathing the freshest air, he sees many objects under his feet, looks at the immeasurable space of the Ocean, dreams of his own ambitions, bringing himself closer to the whole world and those distant countries that he left. There, I thought, beyond these high and wild mountains, beyond this vast Ocean, beyond the greatest expanse of land, there live my relatives, my friends whom I will see again. Such thoughts gave me extraordinary pleasure and brought my soul into such a sweet thrill as I had never felt, and which, it seems to me, a resident of St. Petersburg can feel only in America, in this remoteness, where everything that he meets is completely new to him, and his imagination disposed to dream.

From here we went down along the ridge to the river, along the bank of which we reached the so-called Sapozhnikov dwelling, located seven versts [a verst, remember, is about a kilometer, so call this four miles –JT.] from the harbor, and so named for the promyshlennik Sapozhnikov who lives there and oversees cattle breeding, fishing and other things. The mountains in this place are quite far removed from the seacoast, and the valleys, extending to it, consist of very good and fertile earth; for which reason, in addition to a lot of haymaking, they tried agriculture, but fogs, or ignorance, have caused the success of this to remain doubtful so far. On the way from the mountain to Sapozhnikov's dwelling, we were caught in the rain, and we got even wetter fording several streams flowing through the fields, so, to return to the harbor as quickly as possible, we went in a baidarka.

8 March.

At 8 o’clock in the evening, the northern lights began, going from the northeast to the north, and at 4 o’clock in the morning there was a slight earthquake; only two tremors were at all strong.

18 March.

The wind was blowing pretty strongly from SE with snow, but in spite of that I set off from the harbor with three baidarkas. I visited the Americans of the southern Chiniak village, then traveled all over the bay, where these dwellings lie. Heavy rain forced me to return to spend the night in the same village of the Konyag. This is what the inhabitants of Kodiak call themselves.

19 March.

In the morning it was snowing, raining, hailing, and sometimes the sun shone through; then the snow continued without interruption.

20 March.

When the snow stopped, I set off to hunt on the inner bay, sticking to the shore in different places; for everywhere partridges were found in great numbers. Meanwhile the wind from the north began to grow stronger, and I raced to the harbor. Soon the storm intensified and the disturbance became violent. We were still far from the harbor. Almost every wave doused us, and water often got into our mouths; but most of all our hands were frigid, for in the severe cold they were continually wet. When we shifted our oars from one side to the other [these were the same type of double-bladed oars we still use in kayaks –JT.], they were almost pulled out of our hands. In addition, the Americans, who were sitting in my baidarka, managed very skillfully without worrying, and at every coming big roller they shouted: ku, ku, ku! so, I think, as to warn their friends. One roller tore off my sprayskirt [Here I’ve used the modern term for the seal around the kayaker’s body, which fills the opening. The Russian word here, obtyazhka, means a tight-fitting cover, and most often refers to upholstery –JT.] and half of the baidarka filled with water; but fortunately, another baidarka soon rowed up to me and straightened everything again, although it was no longer possible to bail the water. Finally we approached the cape of the island lying near the harbor, but we could not go around it, because of the great waves striking the rocks of that cape. My comrades in other baidarkas went down to the bay, and I stubbornly tried to go straight; but my baidarka was almost thrown on a rock, so I was forced to follow them. There we were carried across a small isthmus and at one o’clock arrived home, wet and extremely cold from head to toe, so that we could not quickly dry our hands off.

28 March.

In the morning I set out from the harbor in very good weather, but soon it became cloudy with a fresh wind, and it rained for half an hour. I had to cross the strait between Kodiak and Afognak, which is about 18 versts wide. On Afognak we landed at the Rubtsovaya Odinachka, where a Russian hut was built – those places where there is no settlement of native inhabitants are called Odinachki; one promyshlennik lives there with several Mushers [as in dog-sled drivers –JT.] In summer he looks after hunting, and in autumn he traps foxes.

29 March.

A strong wind from W prevented us from going further. Today I dined very well, for I shot many ducks and little sandpipers, and yesterday I caught a crab.

30 March.

A harsh wind forced me to stay here all day. However, despite the severe weather, I went to hunt near the shore. At the beginning I winged one duck, which I chased for a long time, finally losing sight of it. Then, having moved on, I killed several more birds, and on the way back I saw the duck that I had shot earlier, and began to chase it again. It got tired, was already diving weakly and once appeared out of the water so close that I wanted to hit it with my oar, but leaning too far I lost my balance and capsized the baidarka. I spent some time in the water upside down, until, having freed my legs from the bindings, pushed with them, and I emerged quite far from the baidarka; the heavy clothing I was wearing plunged me to the bottom, and at first I could not come to my senses, choking on the sea water; but two of the Americans caught me by the collar and dragged me to the overturned baidarka. We all grasped it with our right hands and rowed with our left, and thus made it to shore. After this they caught the duck, the culprit of our unfortunate adventure; but meanwhile my clothes froze over and, leaving my rowers, I ran to the village of the Konyag, about a verst away: there I dried my clothes and warmed myself.

USGS Map of the northern part of Kodiak Island. – US Geological Survey

31 March.

At 6 o’clock in the morning I set off in clear, calm, but very cold weather. From the strait located between the islands lying on the northern side of Kodiak, we saw the snowy mountains of Alaska (or Alyaksa), many of which, at a distance of 60 or 70 miles from here, seemed higher than the highest mountains on Kodiak. In general, the entire coast of the Alaska Peninsula is extremely high, and because of this, winters there are incomparably harsher than on Kodiak, which is separated from Alaska by a strait of 40 miles. Having passed those islands, we began to circle the large Kodiak Cape, which juts out far into the sea. Whales were playing around it, and some of them came up so close that we could smell their breath, which had a very disgusting odor. After that, we rowed past Uganik island [a good-sized island near the western part of Kodiak], and we wanted to go around Cape Kuliuk [west of Uganik Bay], but a fresh wind from the west and rather high waves forced us to descend into Uganik Bay. In the evening it was cold and I froze my right hand badly, for the waves coming from the other side often poured over it, and I was very lightly dressed. We arrived late at the Uganik village, where we settled down to spend the night in an empty house, which was abandoned by the Americans because they say that noise is always heard under the floor at night, and that a ghost comes out in the form of a woman, with loose hair and with a covered face, except for glowing eyes. But I was extremely tired from strenuous rowing, fell into a dead sleep and did not see any ghost.

1 April.

In the morning, in cold weather from the west, we set off and rowed around a long cape, so that later we would turn into the strait separating Uganak Island from Kodiak. But as the strait is very far from the village on that island, we landed on the opposite side into a small bay, crossed the island on foot, no more than three versts to the village; we carried the baidarkas ourselves.

2 April.

A strong north wind delayed us here, but I was not in the least upset about it; for it makes no difference to me whether we are in one of the islanders’ villages or another. In the evening, the Alaskans who were staying here with several residents danced the Kuliuk dance. I regaled everyone with tobacco, and one old man got up and thanked me for everyone. During the day I went with a gun or played with the natives in their game called Kaganak, a description of which we will see later.

It is known that the Konyags are not so much afraid of death as of being flogged. Soon after our arrival at Kodiak, a promyshlennik was whipped for insolence and disobedience by the cat. From that a rumor spread among the Americans that we had brought such whips from Okhotsk, which were hurting them. One of the locals came to the sailor who was with me and ask him: is it painful to be flogged with the cat? Try it, he answered. The islander left him, but soon returned with a thin woven rope from home, and giving it to the sailor, he asked to be flogged. The sailor, finding such a request very ridiculous, had the American lie down, and with the rope folded in two, he hit him three times with all his might on his bare back. The Konyag jumped up and immediately disappeared, not, of course, with a very favorable opinion about punishment by the cat.

3 April.

I went in a baidarka to a small enclosed bay jutting into Uganik Island. It seems to have been made by human hands: its mouth is just like a fortress’s open gate, carved into a stone breastwork, and is no wider than seven sazhens, although it is quite long. The current in this place is extremely fast, and when at low tide there is no more than three feet of water, it has a very noticeable slope to the sea and seems to have been lowered through a sluice. The banks of the channel or mouths of the bay are vertical everywhere, beyond which is the bay like a ladle, in the middle of which lies an island. In the surrounding area grows a forest, and bushes grow along the banks. With great difficulty I ascended this channel, although at that time the water was quite high; descending along this into low water, I had to rely only on the oars, for it seemed that I was floating along a rapid, where the turbulence from the swiftness of the water became completely crushing.

4 April.

At 3 o'clock in the afternoon the wind became calmer and I set off for the harbor. Before the tide turned, I had to wait at the Bystry Strait, named after the strong rapids in it, against which the baidarkas cannot paddle. When the water subsided, we set out on a journey. I dozed off, but an extraordinary noise woke me up. The reason for this was a small whirlpool at the end of Bystry Strait. We had to pass it with great caution, supporting the baidarka with oars, so that it would not be overturned by the waves. The night was very calm and clear. When the baidarkas became separated, I fired my gun, so that they would come back to the sound. Our journey seemed very pleasant, and we crossed the strait obliquely between Kodiak and Afognak, although in this direction its width would be about 25 or 30 versts. I shot a swan right next to the harbor, to which we arrived at five o’clock in the morning. From Uganik Island it is estimated about 90 versts to the harbor: and we covered this distance by rowing for less than eleven hours, not counting the time that we stood at the Bystry Strait.

This is the second of three installments during Khvostov and Davydov’s stay on Kodiak. Next time they will continue their winter and early spring diversions on Kodiak, before finally making their preparations to return to Okhotsk.