The previous episode:

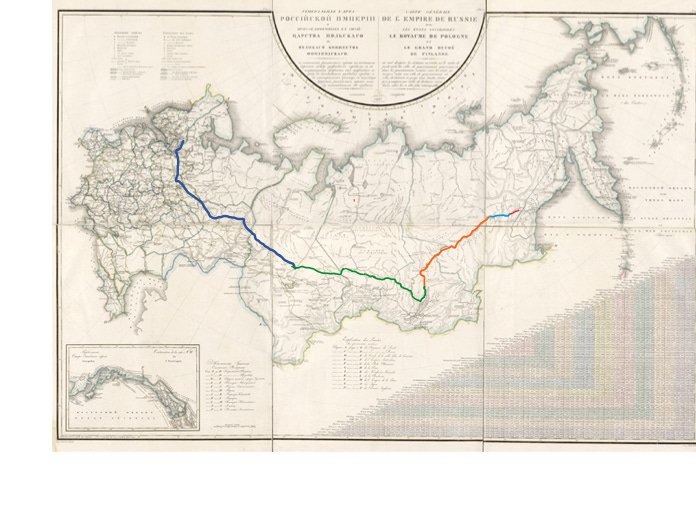

Having reached the Aldan River, our heroes now begin the arduous crossing of the spine of the Stanavoi Ridge. The terrain is difficult, and many of the streams they now have to cross have multiple channels, as often happens with glacial runoff in northerly regions. Davydov is becoming impatient, and his usual deadpan humor is beginning to give way to sarcasm.

As the country becomes wilder, so do the people and animals they encounter. They also no longer have the benefit of regular post stations at which to refresh themselves and change horses, so now they have to bivouac. Naturally, it also seems to rain pretty much the whole time, and they always seemed to be going uphill.

DAVYDOV’S NARRATIVE (Cont’d)

[17 July 1802, cont’d]

On the Aldan, we found 6 horses hired for us by the company at 50 rubles each, and we took one spare, or zavodnuyu (maybe something like exchange) as they call it here, and further 10 post horses – we weren’t able to muster any more than that fit to withstand the journey – and with them 4 Yakuts especially for the horses. With us, for safety, went the mail. The fastest rider can make it from Yakutsk to Okhotsk in 10 to 12 days, but more commonly the Yakuts take from 18 to 20 to get through. Most of the freight is sent from Yakutsk at the end of March or April, and the caravans cross Aldan on the ice. The horses then are at their thinnest, walk very slowly and stand idle for a month when they find good forage. These convoys will be called formations, and horses are cheaply hired at that time. The goods that come to Yakutsk after the opening of the Lena are sent from the Yarmonka, which is opposite Yakutsk, (where they load the carriages) and so they are called by this Yarmonchnims; at that season they pay 15 to 25 rubles or more per horse. The so-called light horses are hired more expensively than this, for when you need to get to Okhotsk quickly, for this the horse can carry no more than 3-1/2 or 4 poods. So many cargoes are brought from Yakutsk to Okhotsk, and so few of them come from there that most of the horses return unladen. At Okhotsk the Yakuts usually fatten them up, and on the seashore, where the grass is somewhat salty, they are fed to excess for 15 or 20 days. Then the Yakuts are hired very cheaply, so as not to go for nothing, and sometimes undertake to deliver them in eight days from Okhotsk to the Aldan.

This day of rest revived me, so that I no longer felt any pain in my arms and legs. We, like sailors, exhausted from illness, coming into port after a long voyage, recuperated and set off again, with new hope for our strength. We left at 10 o'clock in the morning.

The unfamiliarity of this road inspired me to collect all the names of the low places [this is an odd Russian word urochishch, meaning a distinctive place, and perhaps a swampy one –JT.] along it and describe them in full detail. These names are given by the Yakuts. The Russians call the distances between these places dnishcha (bottoms) and the Yakuts kos. The Russians always believe a kos is about 10 versts, but of course this calculation is not correct, because it came from how many Yakuts pass per day in the spring on the worst horses. And so anyone can see that such a dimension cannot always be the same. At each kos, the Yakuts notice some place and give it a name.

10 versts from the Aldan there is a ridge, very muddy during the rains, called Linka-Yyabyst, which is 10 versts long. Then, after 10 versts the Berchzhigis Ottu (pine forest), and 10 versts further a ford across the Belaya [White] River, which flows into the Aldan. The ford is only passable at low water, but after the rains this river (like everything that flows here from steep and not far-away ridges) overflows to an extreme, so that it is necessary to keep transports on the Belaya and on many other rivers, but their officers usually let them go, and thus greatly slow down the passage, so that convoys at other rivers stand idle for 10 and 15 days and even, there were examples, more than a month.

We had already crossed several branches of the Belaya River and were within a verst of completing the ford, when suddenly a Yakut, galloping to meet us, told us that on this side of the river near the ford there were more than 10 well-armed Varnaks, that they had caught him with the mail, held him bound for more than a day, and that the postilion was gone. The Yakuts volunteered to take us on another ford past the Varnaks, and we willingly agreed to this proposal, for it is unpleasant enough to ride 700 versts across the desert on horseback, and would be even more so if we happened to be attacked by robbers.

Crossing the Belaya by the other ford, we rode through a very dense forest and marshy swamp. In a short distance we left behind a bear, which was about as friendly as the Varnaks. Finally the horses were so tired that many were already falling and we were forced to spend the night in the middle of the swamp. We had just gone to bed wrapped in our greatcoats when it started pouring rain, which soaked us through in a quarter of an hour. I ordered myself to be covered with a felt of grass, which they put on horses under saddles and are called potnikami [the Russian word today now means sweatshirt]; this did not give me much warmth, and after half an hour the rain soaked through so I could not sleep anymore. The piercing cold and dampness made me tremble and tormented me tremendously.

19 July.

The night seemed like a year. Day arrived; none of us had slept, but we did not talk to each other, because nobody wanted to raise his head or move; for with any such change of position, the cold became more acute. I lay huddled until the moment I heard that the horses were saddled and ready to ride. Then I saw that none of my companions was in the best condition, for all stood near the dying fire and shivered from the cold. At 10 o'clock in the morning we set off. I clung to my horse and envied the one who sits in a warm room without thinking about the rain pouring down like a river. I would have given everything that I had just to hide in a hut sheltered from the rain. To many, this weakness will seem ridiculous, but let them think about it after they hadn’t slept for 1-1/2 days and after spending more than half of this time in the rain, without a dry thread on them: only then can their conclusions be fair.

The mud increased greatly, the dells that were dry the previous day were filled with water and turned into swift rivers, which we had to ford. To our consolation, we hoped that we had left the Varnaks behind and they would no longer bother us, especially since at the time all our guns and pistols were completely frozen.

Having ridden five versts on our way, we stopped at 1pm to feed the horses. We barely had time to pitch a tent and start a fire, when we heard nearby two rifle shots, at which our Yakuts immediately fell on their faces, and at the same time seven people appeared from different sides, two of whom walked straight to us, having guns quite ready. Not expecting anything good from such a meeting, we began to grab hold of our frozen guns. Khvostov could not get his quickly enough, so raising his saber he ran to meet them and went up to their chieftain and asked, What do you need? How dare you approach these military people? Put down your gun, or I'll order them to shoot you. This bold act frightened the chieftain. He ordered his comrades to put down their guns and said: we see that you are military men, and we do not demand anything from you. The other robbers also shouted to us, don’t shoot! Don't shoot! Meanwhile, however, the ataman, looking with some surprise at Khvostov, invited him to go with him to their tent, which, according to him, was no more than a hundred sazhens from this place. Khvostov, so as not to show himself intimidated by this proposal, answered, let's go. He went with them to the tent, where ten more men were gathered. One of these began to speak rudely to him: you are a young brother, but make a lot of noise: and began patting him on the shoulders. Khvostov, seeing that this insolence might also encourage the others, decided at that moment to hit him on the cheek with all his might, so that the robber could not stay on his feet. Then he raised his saber and said, if you think of doing anything against me, you will not deal with me cheaply, I can deal with you by myself, and moreover, my comrades are at hand. The robbers were dumbstruck. The Ataman shouted at the culprit, saying to him: we forgot that we are Varnaks, and his honor is the Sovereign’s officer. Then he ordered him to bow at Khvostov's feet and ask his forgiveness. Thus, peace was concluded with the robbers, who then not only did not even think of taking anything from us, but themselves offered us everything they had except their sugar, which, they explained apologetically, they had not taken from any merchant. We did not accept their offer, but told them not to think of doing anything stealthily, if they wanted to treat peacefully with us; but they assured us that they would not go away and do any such thing, and that they were not at all such robbers as we imagined, but that they had fled from extremity and hard subsistence; that they only took what goods they needed from the merchants; and that they would never dare to kill anyone, otherwise than to defend themselves.

20 July.

In the morning we set out without any disturbance from our neighbors. At 10 versts from the ford across the Belaya, which is called Sergakh Sibikhta, then Siyallyakh Tumul (hanging manes), 10 versts farther Otyrchzhas Tuch, and later Syullyakh Tumul (muddy place), a ridge so called because in rainy times, it has awful mud and deep liquid swamps. The recent rains produced so many streams that it was necessary to ford them, as with the many branches of the Belaya. All these flowed extremely swiftly and had rocky bottoms. It was impossible to cross one stream at the usual place and we searched for another, going round the swamp. Having found a likely place, we began to cross, but many horses got stuck and fell into the water, soaking the whole equipage, which we pulled out, getting ourselves wet.

All goods and things transported along the Okhotsk road are packed into bags made of cattle skins, the seams of which are so well covered with pitch that nothing put into them will get wet, even if the bag falls into the water; but as the Company did not have to worry about saving our equipage the way they would their own goods, and we didn’t understand anything about it, then we were given, as if on purpose, rotten and torn bags, in which most of the contents were completely ruined.

Then we entered Bvstyn Kharatit (first black forest). There are three of these Kharatits in a row, each about 10 versts long, and the last a little more. Passing on the left side is a rocky mountain, called Tyllakh-Nyura (windy rock), because a stiff wind almost always blows near it. In the evening, passing the river Mukhtulu or Kondratov we stopped to feed the horses at Orto Kharatit (second black forest). In order to move to where we settled down to spend the night, it was necessary to ford a stream first. To find out if it was deep, they sent a man who was at the post station to guard the Yakut, armed with a bow. They call these batasta (armor-bearers) (* - this warrior was so brave that earlier, when we heard about the proximity of the robbers, he deliberately cut his bowstring in order to have an excuse not to act on it.) Although the river is no more than 2½ sazhens wide, and usually completely dry, however at this time it was so deep that the batasta had to swim across it: for which reason, having untied the horses, we drove them into the water, while we carried our luggage and saddles, putting trees across the stream.

Instead of the word brat (brother), which we use when addressing someone, along the Lena they say tovarishch (comrade), and the Yakut Dagor, that is friend.

21 July.

In the morning we got up from that place. Around noon it rained, but soon abated and the sky again cleared. We rode between two ridges, descending where the river Chegdalka flows out of the Chagdal ridge, which we crossed up to 15 times by fording, the same as the number of streams flooded from the rains. Chagdalka flows into the Belaya. The post horses were so thin that we were obliged to leave one of them on the road to Yakutsk; On the other hand, the hired ones are all very good, so if they were all such, then surely we could move from 60 to 70 versts a day, which means a lot along such a bad and stony road, where unshod horses soon break their hooves.

Sometimes we picked a lot of blueberries and red currants, which they call sorrel, looked at squirrels and chipmunks (animals smaller than squirrels, their skin is red-gray with white stripes), which our dog looked for and drove up the trees, which served as our only escort for a time. Occasionally we shot the game we came across.

The mountains that presented themselves to us were varied – some ended with sharp peaks, like sugar peaks; others had the appearance of domes, some were overgrown with forest, but most of them were covered with small stones. Sometimes the ridges on both sides shifted their position so often that it seemed as if we were surrounded by mountains from everywhere.

At 7 in the evening we stopped between two ridges near the river Chagdalka. The Yakuts usually let their horses stand two or three hours before they turn them out to feed; if they are very fat, then they keep them on a tether for a day or two before they set out, and even after that, from the beginning of the journey, they give them very little time to graze.

Thunderclouds appeared in the west and a storm soon set in. The clouds moved in different directions near the tops of the mountains, the echoes repeated the crack of the thunder in the various valleys; all this together presented a magnificent and terrible sight. But the wind soon changed and dispersed the thunderclouds, and the rain continued until 7 o'clock in the morning.

22 July.

From the Belaya River, we drove almost continuously uphill along an extremely difficult road, at places the most fruitless, where occasionally only a little faded grass appears. Today we forded Chagdalka ten more times and began to climb the Chagdal ridge along the edge of the gorge, from which the mentioned river, past the top of which we drove here, rises higher. Having climbed the mountain, the same hour, we began to descend with it along the hollow, where a large stream flows, which flows into the Yunikanka river, which runs out of the Yunikanskiy ridge and flows into the Belaya. Having crossed this stream many times, we approached the first ford through Yunikanka, which will be about 155 versts from the Aldan. The space between the Chegdal ridge and the aforementioned river of the same name is called Chekhonoev's lament, because once near it bears killed all the horses of the Yakut Chekhonoev, and the Yakut cried about it here. This place is one of the three at which most of these beasts are found. The other two are Prodigal Ridge and Empty Ford.

Traveling for some time along the Yunikanka, we saw mountains on three sides. On the left ran a ridge, around 150 fathoms high, consisting of limestone and completely sheer; the one on the right was somewhat sloping, higher than the first and covered with fine stone. We turned to the right, where the mountains were no more than 50 fathoms apart from one another, and the one on the left is made of limestone and looks like ruins. Many of these overhang so much that it is dangerous to drive near these mountains, but the Yunikanka flowing in the middle does not allow us to leave.

We forded it on this day more than 20 times, and at 10:30pm stopped at a place called Pribilov’s Anbar (warehouse), because once the merchant Pribilov built here an Anbar for warehousing goods, of which there is no longer any sign; he also placed the cross that still exists to this day on the nearby mountain with a completely conic appearance.

Although our horses were very tired, we went further, because we could not find any fodder; for there was hardly any in these mountainous places. The road consisted of high uneven rocks, so that the unshod horses stepped with extreme difficulty, and often break their hooves and become incapable of continuing the journey.

Down Yunikanka at one place lay ice that never melts, and on many mountains and in hollows snow was visible.

23 July.

At dawn it rained, and at 7am we set out on our journey; we forded Yunikanka five times and began, along a road filled with sharp stones, to climb Yunikanska ridge. The rise is quite gentle. The view from the top of the ridge is beautiful. Looking at it, I forgot about the rain that had soaked me to the bone. A terrible abyss separates the two mountains, from which the Kunkui River flows with a noise, falling into the Belaya: gradually in the distance ahead many rows of mountains appear to the gaze, one larger than the other, with sharp or dome-like peaks rising above the clouds. All this presents such a spectacle, to which the view of the Alpine mountains would yield, if it was described by many travelers, except that there is no one here to experience these rarities of nature. Haze prevented you from looking clearly at many more mountains that appeared bluish through it. The tops of all are bare, but some ridges are half covered with larch.

The descent from the Yunikanska ridge is very steep. We rode with the Kunkui on the left side; then we crossed by ford more than 20 times the several streams flowing on it. Sometimes I couldn't get enough of the magnificent and terrible views in these mountainous places of the Stanovoy ridge, revered as one of the highest on the globe. What a variety of food, at almost every step, a skillful painter or descriptor of nature would find for his brush or pen!

Heavy rain, strong wind and piercing cold, which can happen in summer at such high places only, exhausted our strength to the point that we could hardly listen to the Yakuts, who wanted to go farther to find food. Again we approached the Belaya and crossed it eight times. After the first ford, we rode across the river Byukyakyan, flowing into the left side of the Belaya. Between the 4th and 5th fords on the Belaya there is a lip higher than a fathom; and between the 6th and 7th is another one smaller than that, and many still smaller. The current at the top of this river is extremely fast, and the rains that have happened recently have contributed a lot.

In other places, Belaya flows with fog, between the rocky banks, as if through a gate, and presents a very beautiful view.

At 7:30 we stopped, immediately built a fire, pitched a tent, threw off our wet clothes, began to warm up, cooked a gruel of black bread crumbs with ham and began to eat it. The reader naturally will not envy our condition and will not find it superbly prosperous, but at that time it seemed to us more excellent than all that luxury and delicacy can invent. The fire and the tent were better for us than the most magnificent palaces, and the gruel of rusks tasted better than any sweets. They had such a high value in our eyes after we rode on horseback for fourteen hours, hungry, in heavy rain and a strong piercing wind. Such cases are felt more by the one who endures them than by the one to whom he later retells them. However, they teach work and patience more than all eloquent instructions. A person who has the means to ease his suffering does not endure it with such firmness as the one who endures without any hope of relief. This very impossibility to change our condition bolstered us and forced us to say to each other, what to do? a life to live, not a field to cross. Setting out on a long journey, one must consider any need that is endured as a useful trial, alleviating the burden of those labors that may happen in the future. On top of this, a person who has lived his whole life in uniform peace is deprived of the pleasantness of remembering the changes that happened to him. Such thoughts filled us on our way, and delicious gruel was our reward.

24 July.

Waking up early we were very glad that the rain had stopped and the water in Belaya had fallen a lot. A Yakut driving cattle to Okhotsk and staying the night not far from us, brought us milk in the morning, for which we gave him some money and tobacco, which he immediately crumbled, mixing in a few shavings. The Yakuts love Cherkasy tobacco, but always smoke it cut with shavings. Every Yakut has a copper pipe, which holds no more than a pinch of tobacco. The pipe fits onto a wooden handle, consisting of two grooves, tied with a belt. Unfolded, the handle breaks down into two for convenient cleaning. The burned tobacco in the pipe and the char from the smoke they do not throw away, but again mix with the shavings and smoke. Yakuts swallow the smoke, which sometimes makes them so lightheaded that they fall off their feet. On the belt, where the pipe is tied, there are also iron tweezers, with which the Yakuts pluck out their beards, another sack with tinder, consisting of dried wormwood, and a small knife with a wooden or bone handle.

At 10:00 we set out, forded Belaya 20 more times, and began to climb the first of seven ridges: called the seven mountains, one after the other. Sometimes we rode along the river itself, when the mountains on both sides were so close, that between them and the river there was no other road. The summit of the first ridge is like a semicircle, in front of several others which can be seen, so that the further they were, the higher they became, and the top of the last one was

hidden in the clouds. We began to descend in the place where the Akarsk river rises, which flows into the Allakh-Yun. The first of these, along with many streams flowing into it, we forded several times. At its head were visible small waterfalls. Some of the streams, falling with rapids from high steep mountains, noisily hit the large hanging stones, presenting to the eyes the most beautiful picturesque scenes everywhere.

At 10pm we arrived at the Allakh-Yun river, located 233 versts from the Aldan. It flows into the Maya, which flows into the Aldan. We landed at a lean-to or at a cover set on several poles near the ferry across the river, which, however, in the fall they pass by fording. The Yakuts did not want to go to the station, because many horses were overcome by infection near it. We barely had time to fold under the cover when it started to rain.

Allakh means nimble, and not without reason is this river so called, for its current flows swiftly.

Although the last rain was not great, the water in the river was much higher.

In the summertime Allakh-Yun has post horses, which only go out under couriers, postal or relay; which is why travelers are forced to ride from the Aldan to Okhotsk on very thin horses, or to take them on the road by force from the povorotchiks (turners). This what they call the Yakuts, who took goods under contract to Okhotsk, fattened their horses there and returned to their uluses unladen, unable to contract to carry anything from Okhotsk. These “turners” usually collect in court from the station postmasters very dearly for the horses taken as they pass, but the litigation goes on for so long that no one profits, and therefore, to avoid the hassle, the turners return to the uluses by roundabout roads; when they are forced to ride the high road, they always have two or three people on the best horses ahead of them, several versts away. These people, when they meet anyone, race back to inform their comrades, who are hiding to the side with the herd.

Before Allakh-Yun was settled there was a Cossack, who changed horses and sold food, and although he greatly enriched himself, however the Yakuts and travelers at that time derived much benefit from him, of which they are now deprived.

60 versts from the Aldan, begins a road of uneven stone, continuing to Allakh-Yun, from which many of our horses knocked out their hooves. In addition, for some distance there is not a single decent source of feed, and for these two reasons several horses were rendered completely incapable of continuing the journey. It is a good thing that some were changed already at the convoy that we met from the American company.

25 July.

Unable to find many horses and the only boat having been swept away by the current, we were forced to stay at Allakh-Yun. The rain stopped at about noon. At our leisure, we picked blueberries and currants.

In the next installment: Chapter II of Davydov’s narrative continues. The country they are traversing becomes still wilder, and their experiences a bit more unusual. Next time Khvostov and Davydov meet more robbers, deal with nomadic Tungus, and learn to ride reindeer, Tungus-style. And it keeps raining.