My spouse and I have just returned home from a long weekend in New York. We always try to take full advantage of the city’s cultural and entertainment offerings, and this time around our activities included a Broadway musical, an opera at the Met, and some Shakespeare. Here are a few impressions:

Broadway Musical: & Juliet, Stephen Sondheim Theater

This was a surprise treat:

At a basic level, & Juliet is a high-energy jukebox musical (the pre-show tableau on stage features a jukebox) with a big dose of Broadway spectacle. Many in the audience doubtless received it that way, and welcome. But there is a lot more to it.

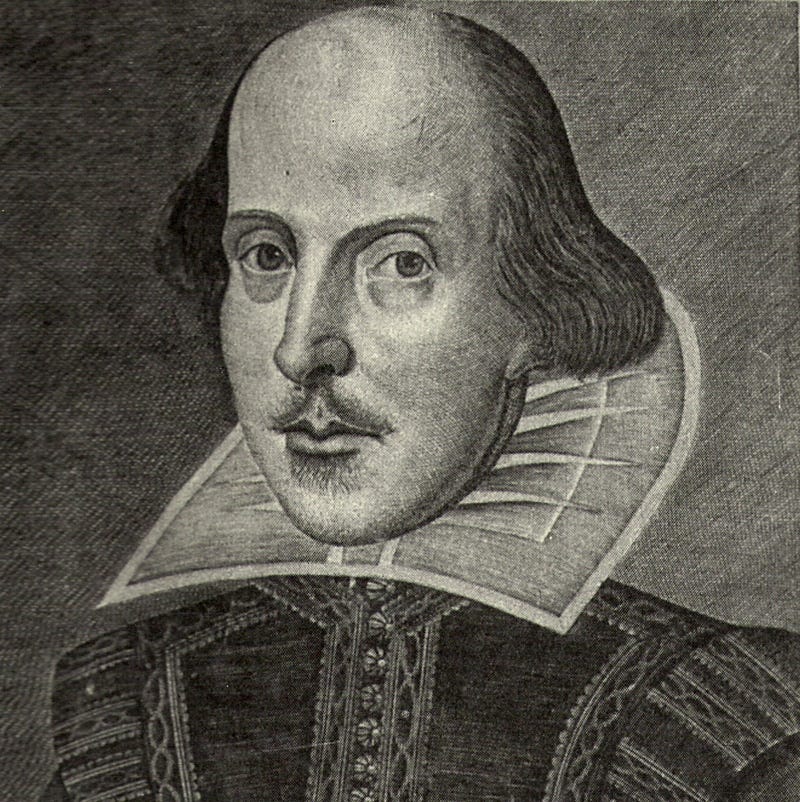

The conceit is that it’s 1595, and Romeo & Juliet is about to premier. Shakespeare, as always, is finishing it just in time, but Anne Hathaway has popped down from Stratford, and she doesn’t like the ending. It’s ok with her that Romeo dies, but she thinks Juliet should survive and get on with her life. The Shakespeare-in-amber crowd would get up and leave at this point, but the piece makes a strong case for Shakespeare as our living literary patrimony. & Juliet won’t outlive Romeo & Juliet, but it’s a fine entertainment for our time. The creators of the play clearly know and love Shakespeare well enough to have confidence they can push him around pretty hard and he’ll remain standing.

Anne grabs the quill Will (if I may - they do) is holding and starts to spin out a plot, which the rest of the company enact as they go. The quill passes between Anne and Will several times, and serves as a token denoting who’s writing now. Anne and Will both end up writing characters for themselves to play, so when they step out of those characters to be Will and Anne as themselves, they may be breaking sort of a third-and-a-half wall, but the fourth remains intact, except for the occasional Shakespearean aside.

The script brings along those less familiar with Shakespeare without taxing the patience of the cognoscenti. Anne introduces a trans character (who ends up being important), and when Will balks, she says something like, “You of all people - you’re famous for having men play women, who are dressed up as men half the time. You’re synonymous with gender-bending!” There are Shakespearean references all over the place. Some are silly - one character wears a ludicrous codpiece most of the time; when Juliet and her posse decamp from Verona to Paris in a coach, it has a British-style number plate reading “2BN2B VR;” and there are vile puns throughout. Some references are direct and obvious - when Juliet’s parents learn that Romeo is dead and she is alive, they decide to send her to a nunnery (which is why she bolts for Paris). Some are more subtle - Juliet falls in love with a Frenchman named DuBois, constantly pronounced De Boys, and in the slyest bit of gender play she sometimes wears a skirt that looks like a doublet.

There’s just enough bad language, lightweight bawdiness, and the aforementioned gender-bending so that the folks from the hustings can go home feeling they saw what they came to New York City to see, secure in the knowledge that they won’t have to see such things at home (until their local Shakespeare company stages Twelfth Night or Merry Wives of Windsor).

My favorite scene is between Anne, as her character in the play, and Juliet. Juliet is asking Anne's character for advice, and Anne doesn’t know what to tell her. At this moment Anne realizes what Will has always known - that you don’t just get to make your characters do whatever you want them to - you have to get to know them and then let them decide.

This is a good choice for a tourist on a rare trip to New York, who wants to see one Broadway show. In the world of jukebox musicals, it’s literate and funny. Only Shakespeare-in-amber types should stay away.

Opera: Moby-Dick, Metropolitan Opera

This was the one disappointment of our theatre week. This adaptation of Herman Melville’s novel, by Jake Heggie and Gene Scheer, premiered in Dallas in 2010. The idea of adapting the novel for opera has its appeal, especially considering the success of Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd. But instead of accessing the power of the form to produce a compelling new viewpoint from which to examine a great story, Heggie only managed to give us a stripped-down version, with music. Melville dedicated his novel to Nathaniel Hawthorne. The legend is that he showed Hawthorne an early version, and Hawthorne encouraged him to develop what was a pretty good fish story into something far more consequential. The opera came out as though Heggie had stuck to the original fish story. Toward the end, the libretto does try gamely to remind us that Moby-Dick is one of the great works of American transcendentalism, but it was too little, too late.

Part of the problem is that the elements of the opera – music, orchestra, singing, acting, mise-en-scène, and story – were out of balance. One of the things that makes opera special is the use of music to tell the story. In the first half, the music conveyed the relentlessness of the sea, but the corresponding relentlessness of the music conveyed nothing of the tension of the story. The second half was better, but there were no real musical highlights – no memorable arias, and only a couple of interesting duets. I separated music from orchestra and singing in my list above because the orchestra was, as always at the Met, on point – the weakness of the music wasn’t their fault – and some of the singing was quite good. Ryan Speedo Green sang well as Queequeg, and acquitted himself well as an actor, too. I also liked Thomas Glass as Starbuck, and the lone woman in the company, Janai Brugger, was strong as the boy Pip. Brandon Jovanovich, stumping around the stage on a fake prosthesis as Ahab, probably did about as well as we could expect with the material.

The adaptation stripped down the story far more severely than the designated hitter rule strips down baseball. That leaves mise-en-scène. Unlike every other aspect of this opera, it was over the top, from the more-is-more school. The distinctive elements were the use of projected images and a sloping back wall fitted with rungs up which ensemble members could climb as sailors climbing the ship’s rigging, or to take places in what appears to the audience to be an overhead view of the boats in a whale hunt. The wall also had a large platform that could be lowered parallel to the stage. Its most effective use was in a scene in which Ahab takes to his bed, on stage, while on the platform above the sailors light the fire of the tryworks, rendering the fat from a whale into oil. Ahab’s bed thus becomes a funeral bier.

The trouble is that the orchestra and singers are better than the music, and the staging is too elaborate for the story. I had hoped for more from this opera than it delivered.

Shakespeare: Othello, Barrymore Theater

This is the much talked-about production of Othello, starring Denzel Washington in the title role and Jake Gyllenhaal as Iago. The reviews have generally run lukewarm on Washington’s performance and enthusiastic about Gyllenhaal’s. I can see why, but my take is a little different. If I felt obliged to run Washington down, I’d say that Othello’s transition from complacency to rage was a little too easy, and the rage was too cool - and not quite cold enough. It was as though Othello knew all along what would happen. Washington could have played it that way, leaning on the point of Desdemona’s treachery to her father and playing Othello’s early declarations of his belief in her faithfulness as over-hopeful protestations, but if he meant to do that, I didn’t see it. But all that is just carping, and in the end, it didn’t detract. Here’s why:

It’s always a challenge, I suppose, when a well-known actor plays a well-known role in a well-known play. At times what I saw was not Othello and Iago, but Denzel Washington and Iago. But fact is, I went to see Denzel Washington play Othello as much as to see Othello played brilliantly. I had a similar experience seeing Ralph Fiennes play Hamlet a number of years ago. But this production has an advantage - the play itself. Harold Bloom’s dictum about Othello was that it’s Othello’s tragedy, but it’s Iago’s play - and Gyllenhaal made it his own without upstaging Washington. The only time I saw Gyllenhaal rather than Iago was at the curtain call. During the play it was all Iago at his wounded, cynical, snide, scheming best. Gyllenhaal was great.

I can’t guess what this was like for Jake Gyllenhaal from an emotional or ego point of view. But it can’t be a bad deal for him that Denzel Washington brings him a packed house every performance to see him play Iago.

Molly Osborne was very good as Desdemona - her Broadway debut, the Playbill said, so quite the dive into the deep end. Andrew Burnap was convincingly clueless as Cassio. Of the secondary characters, the best was Kimber Elayne Sprawl as Emilia, who was particularly good toward the end of the play.

The staging was spare, and on reflection I think relied heavily on lighting design. If the intention was to keep the staging out of the way of the play, it was successful. We were there for the Shakespeare and the actors, and the subtle staging allowed them to come to the fore. It was a modern-dress production - the Duke in a business suit, lots of American army fatigues, Othello in an American general’s work uniform (neither fatigues, nor a dress uniform) in the final scene, etc. That can suit the play, so long as the language remains Shakespeare’s, which it did. But Gyllenhaal delivered the early lines (to Rodrigo) “Many a duteous and knee-crooking knave/ That (doting on his own obsequious bondage)/ Wears out his time, much like his master’s ass/ For nought but provender, and when he’s old, cashier’d” with such timeless emphasis on the ass-kissing that I had to go back later and make sure the line was in the original.

So, all the usual superlatives (that’s an oxymoron, isn’t it?) apply. As Nero Wolfe might say, it was highly satisfactory.