A half-century ago, in my first year of college, I had the pleasure of rooming with Don Sanella, who was from Lexington, Massachusetts. Don invited several of us to his parents’ house for a special weekend that spring. After a certain amount of collegiate partying there the night of “the 18th of April in ’75,” we, along with Don’s parents, tumbled out of bed early the next morning to make our way to the town Common in Lexington for the bicentennial re-enactment of the skirmish there – the first shots in our War of Independence. Fifteen years later, when I lived in Cambridge, I liked to bicycle for exercise in good weather, often choosing as the perigee of those rides a circuit of the Lexington Battle Green.

Paul Revere’s ride the night of April 18, 1775, and the battles at Lexington and Concord on the 19th, make up as good a bit of mythic history as you’ll find. They were real events, around which we have over two and a half centuries built stirring narratives and a patriotic mythos. We remember them, celebrate them, and retell the stirring narratives, all with good reason.

Mythic history usually rides just below the level of consciousness, where we don’t realize that it’s informing our view of our world. But when it rises to the level of awareness, it’s worth a closer look. It’s all right to acknowledge that our mythic history might not be exactly factual. It’s true just the same, in that it tells us something about where we come from, who we are, and what we aspire to be.

I moved from Boston to San Francisco in 1991. I knew even then that California is a different kind of place, and that San Francisco is really different. Since then I’ve learned that California has its own mythic history, parts of which lie so deep below the surface that many Californians don’t even know the stories.

One of the things that sets California apart is that our mythic history comes down to us from the hands of professional storytellers. Stories by Steinbeck and Kerouac, poems by Ginsburg, stories and poems by Bret Harte, essays by Didion, and a thousand Hollywood movies all shape our understanding and feelings for California.

I want here to highlight three stories of early California. The first is a fictionalization of a true, but unfamiliar, story. The second, purely fiction, is more familiar, though I think many don’t realize that it’s set in California. In the third, the setting, at least, is recognizable. They’re all told by professional storytellers, but in a mode we don’t usually associate with California: They are three operas.

Юнона и Авось (Yunona i Avos, or Juno and Avos), Alexei Rybnikov, libretto by Andrei Voznesensky, premiered 1981, Lenkom Theatre, Moscow. In Russian and Spanish.

A Russian opera, you say? Yes, and more than that – a Russian rock-opera, in the era of The Who’s Tommy. Here’s the story. In early 1806, Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov, Chamberlain to Tsar Aleksandr I and a major shareholder of the Russian-American Company, was at the fur-trading concern’s American headquarters in present Sitka, Alaska. Conditions were miserable, and the Russians there ill and starving. Rezanov commandeered the Yunona (Juno), a ship he had recently purchased from a New Englander, and sailed to San Francisco to trade with the padres at Mission Dolores for the provisions they needed desperately. Rezanov was also scouting for a site for a Russian colony in California or Oregon.

Over the course of six weeks, the Russians traded with the Spanish for about 75 tons of food, which the Russians took back to Alaska. But while they were in San Francisco, Rezanov, a widower in his early forties, courted (let’s just say) Maria de la Concepción Marcela Arguello y Moraga, the fifteen-year-old daughter of Don José Dario Arguello, the Commandant of the Presidio de San Francisco. By the time the Russians left, Nikolai and Concepción (Conchita) were promised in marriage, Rezanov agreeing to travel to St. Petersburg for permission from the Tsar to marry a young woman not just of another country (Spanish vs. Russian) but another religion (Roman Catholic vs. Russian Orthodox). Rezanov died in Siberia on his way to St. Petersburg. Conchita, though her father received word of Rezanov’s death, never married.

Mural depicting Rezanov with the Arguellos (daughter and father), Post Interfaith Chapel, San Francisco Presidio

Bret Harte, the writer of Gold Rush-era stories and sketches, also wrote quite a bit of surprisingly good poetry about California. One of his poems, “Concepcion de Arguello,” https://allpoetry.com/Concepcion-De-Arguello, embellishes on the story, and Rybnikov developed Harte’s poem and other sources into his opera. The opera takes a good deal of artistic license, as did Harte. To create dramatic tension, the opera portrays Rezanov in a state of moral torment most of the time.

The intersection and conflict between Russian and Spanish interests in California in the early 19th Century had a role in laying the foundations of our history, and the Russian claim to their share of our story is a sound one. We could do worse than to remember those facts of our past through a romanticized tale of a liaison between a middle-aged Russian courtier and the young daughter of a Spanish officer serving on the far side of the world.

Zorro, Héctor Armienta, premiered 2022, Fort Worth Opera, Rose Marine Theatre, Fort Worth, Texas. In Spanish and English.

Can pulp fiction contribute to mythic history? Well, if mythic history is an aspect of our shared cultural memory, then why not? Most of us, I think, have a mental image of Zorro – his swordplay, his all-black clothing, his cape, his broad-brimmed, black hat, and the black mask that he bequeathed to the Lone Ranger, Batman, and countless others. We probably also remember that like Batman, he had a secret identity – Don Diego de la Vega, son of a wealthy landowner. But do we remember that Zorro was a Californian – specifically, a Californio – hero?

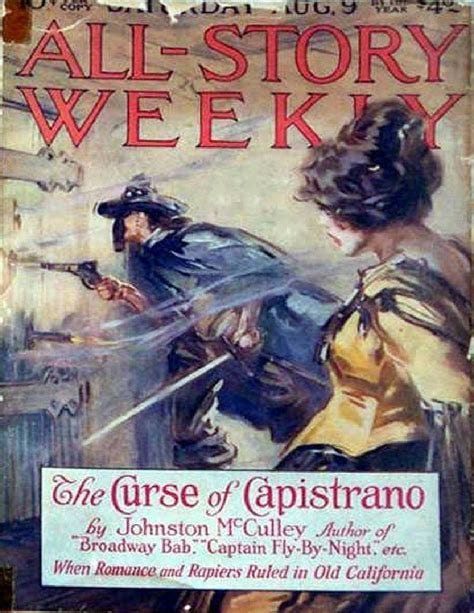

Zorro first appeared in a 1919 story called “The Curse of Capistrano” by Johnston McCully in the All-Story Weekly, a pulp magazine. Hollywood picked up the story, releasing in 1920 the swashbuckling silent classic, The Mark of Zorro, with Douglas Fairbanks as the title character. It was a smash, and McCully would continue writing Zorro stories for another 40 years.

Romance and Rapiers Ruling in Old California.

Armienta’s opera, set in 1811 or so, presents Zorro’s back-story. We first meet him in Spain as Don Diego, where he has just completed his studies with his fencing-master, and he has decided, evidently against his father’s wishes, to return to California. He discovers on arriving at home that his father has died and left him a sword engraved with a motto urging the pursuit of justice. While he has been away, the people of the Pueblo de los Angeles have groaned under an oppressive alcalde, Moncada. Don Diego and Moncada had been friends at the Military Academy, but became enemies in a factional split over the royal succession in Spain. Don Diego reluctantly realizes that his destiny is to fight for the downtrodden and against Moncada and his soldiers. There’s a wonderful trio in which three characters – Don Diego, Moncada, and Ana Maria, Don Diego’s true love, all sing the same words about realizing their destinies, but with entirely different meanings. The first act culminates with Don Diego’s appearance as Zorro, fighting. In the second act, Zorro prevails.

What makes Zorro part of our mythic history is that Don Diego was a true Californio – a Spaniard by citizenship and a noble by birth, but also a native-born Californian. The Californios had a distinct society and culture. Politically, the most important of them felt they owed their first loyalty not to Spain, nor to Mexico, but to California. Some, like General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, would conclude in the 1840s that annexation by the United States would be in California’s best interest. Vallejo ultimately served as a delegate to the Convention that drafted California’s first state Constitution, in 1849. In the time of the fictional Don Diego, California was still a Spanish province, but as Zorro he fought for Californians against obnoxious authority imposed by the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico City and the Court and Crown in Madrid.

La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West), Giacomo Puccini, libretto by Guelfo Civinini and Carlo Zangarini, premiered 1910, Metropolitan Opera, New York. In Italian.

Nothing fills so much of California’s mythic history as the Gold Rush. The list of tales seems endless –Bret Harte’s “The Luck of Roaring Camp;” ahistorical tales of Wells Fargo stagecoaches robbed for their chests of gold (the gold mostly traveled east by sea, not overland); tales of raucous saloons and houses of ill-repute in San Francisco’s Barbary Coast; the legend of Shanghai Kelly (there are many versions, so I won’t link to a specific one, but look it up; maybe the episode of Death Valley Days called “Shanghai Kelly’s Birthday Party” is the place to go).

On top of all the stories, poems, fables, movies, and TV shows about the Gold Rush, there’s an opera. Puccini based his on a 1905 play by San Francisco native and Broadway impresario David Belasco, The Girl of the Golden West. (That’s why we often translate the title of the opera that way, even though it’s really just “The Gal of the West.”) It may be the only opera in the standard repertoire in which the soprano makes her entrance by firing a rifle. (It isn’t the only opera set in the American West with a gunshot accompanying an entrance, but that’s a different story.)

Mimi, the soprano, runs a saloon, the “Polka” (a name perhaps lifted from Bret Harte). There the miners gather for drinks, cards, and smokes after a long day. There’s a romantic intrigue involving the Sheriff, Rance (the bad guy) and “Mister Johnson di Sacramento” (the legendary Enrico Caruso premiered the role), who turns out to be the notorious bandit Ramirrez (the good guy) in disguise. I’ll admit it’s a trope-heavy piece, but let’s just say that Mimi redeems Ramirrez, and through the sheer force of her goodness persuades the miners to let them go off together to start a new life. At the end, Mimi and Johnson/Ramirrez ride off, not into the sunset, but into the sunrise.

There’s much more to say about this opera, but I’ll stick with this. If you love opera, or if you’re interested in California history and you’re opera-curious, see it. Our mythic history concerning the Gold Rush is too vast for one piece to encompass it, but Puccini’s opera at least epitomizes it.

A Concluding Note.

Playing for laughs, Tom Lehrer complained that the old folksong “Clementine” – set, as it happens, in the California Gold Rush – would have been much better had professional songwriters, rather than “the people,” written it. He made a good case, but he missed a broader point about California’s mythic history. Professional storytellers and songwriters – and opera composers – have given us a precious, and growing, legacy of tales, songs, movies, poems, and operas. This legacy is part of the reason California’s history, mythic and factual, is like that of no other place.