If you’ve had the misfortune to hear me talk about my long-term research project in the economic history of California and the Pacific Basin, you’re probably aware that much of my analysis concerns the relationship between commerce and money. My general conclusion is that privileging money over commerce inverts the relationship between the two. Commerce, not money, is primary, and money arises in whatever form is available, or suitable, or simply convenient, to support it. What follows is a brief history, and economic analysis, of the voyages of Captain Robert Gray in the Columbia Rediviva. Gray was the first American sea captain to perform a circumnavigation. On his second voyage, he also became the first to bring a sailing ship into the estuary of the Columbia River, which he named for his ship.

Robert Gray and Columbia Rediviva.

December 17, 1789, Canton (Guangzhou), China – Robert Gray, in command of the ship Columbia Rediviva, had spent the past month in Canton, working his way through a maze of duties, port charges, fees, and finally price negotiations to sell his cargo of “seven hundred indifferent [sea otter] skins and nine hundred pieces,” acquire “a cargo of Bohea Teas for Boston, and expect to sail by the last of next month.”[1] Furs were in high demand during the heyday of the Qing Dynasty, especially toward the end of the 18th Century, and none commanded such high prices in China as the skins of the North Pacific sea otter.

Gray had left Boston over two years earlier and logged more than 30,000 miles sailing around Cape Horn, up to Nootka Sound on the ocean side of Vancouver Island, and across the Pacific to Canton by way of the Sandwich Islands. He would cover another 11,625 miles to return to Boston August 9, 1790 by way of the Cape of Good Hope, completing the first circumnavigation by a mariner from the young United States.

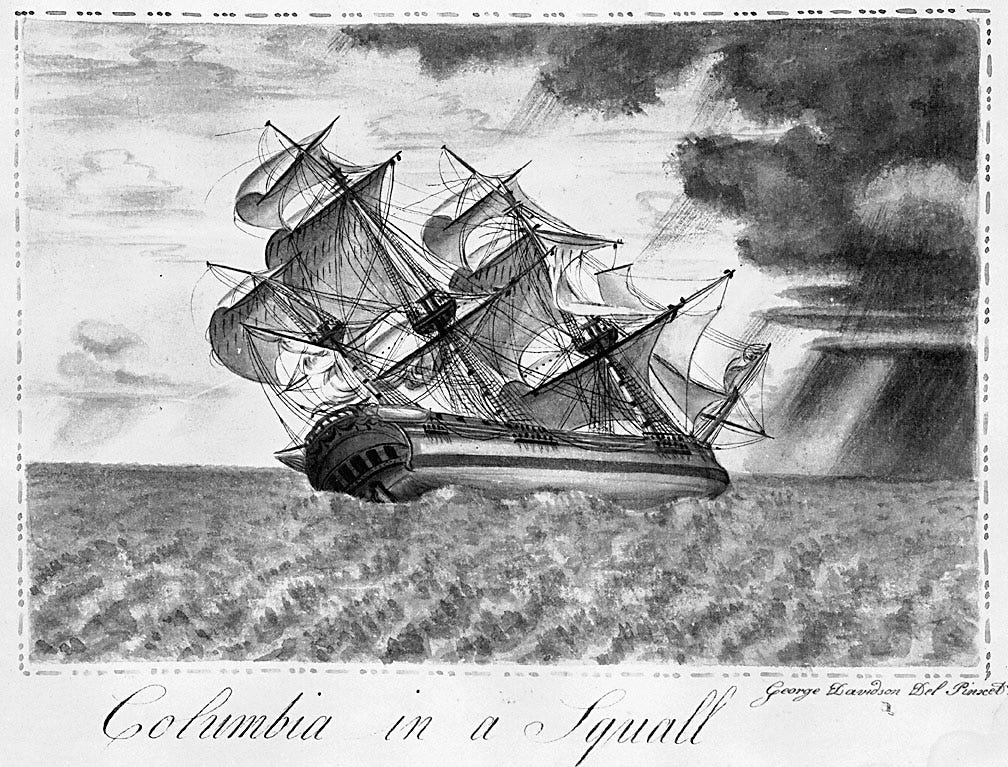

Capt. Gray's ship, the Columbia, painted in 1793 by George Davidson., Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi984.

In the years following the American Revolution, the newly independent States, saddled with debt, their economies disrupted by years of war and loss of their privileged access to markets in the British Empire, fell into a severe recession. The American states’ trade deficit ballooned, triggering a debt deflation, which increased the pressure on heavily indebted farmers and exacerbated the recession. In their examination of the economy of that era, John J. McCusker and Russell R. Menard estimate that per capita GDP of the thirteen states fell by 46% from 1774 to 1790, a decline comparable to that during the Great Depression.[2]

After the War of Independence, the British Government also closed ports in the British West Indies to US ships. This step was particularly damaging to the New England states, as it deprived them of both key markets for such major exports as cod and whale oil, and of a source of supply for molasses, the main input for another of the region’s major products, rum.

New England, with poor soil and a harsh climate, was never an ideal place for agriculture. But the region enjoys rich timberlands, abundant fisheries, and relative proximity to European markets, and so many New Englanders have historically looked to shipbuilding, fishing, and seafaring for economic opportunity. They soon grasped opportunity in the Pacific.[3]

One of the leading merchants in Boston in the years after the Revolution was Joseph Barrell. His trading business included “adventures” to ports near and far – including Virginia, Madeira, Lisbon, Demerara (a Dutch West Indies Company colony in present Guyana), India, and China. On July 17, 1787, Barrell wrote his friend and brother-in-law, Samuel Webb, “I am engaged in a Voyage that will call for a considerable amount of money,” and asked Webb to collect a debt on his behalf to help fund it.[4]

By the end of summer, Barrell had arranged a syndicate, notably including Charles Bulfinch, which purchased, provisioned, and equipped two vessels, the ship Columbia Rediviva under the command of John Kendrick, and the sloop Lady Washington under Gray. The syndication was in fourteen shares, of which Barrell took five, committing £1958 6s 8d.[5] The plan of the venture was to trade iron and simple manufactured goods with the Natives on the Northwest Coast for sea otter skins, cross the Pacific to sell the furs in Canton, and use the proceeds to buy tea, which they would bring home for sale in Boston.

Kendrick and Gray sailed from Boston September 30, 1787. They became separated after rounding Cape Horn the next February. Gray arrived at Nootka Sound on September 17, 1788, and Kendrick arrived a week later.[6] After wintering there, Gray made a reasonable success the next season cruising out of Nootka Sound to trade with the Natives for sea otter skins. Kendrick remained at Nootka.

The trade between the New Englanders and the Natives was straightforward barter. The Natives provided sea otter skins, along with some provisions (mostly fish) in exchange for what the Westerners called “trade goods,” which they had brought specifically for the purpose. The cargo list of the Columbia might have seemed unusual for a trading voyage – it listed hoes, hatchets, axes, frying pans, knives, quart, pint, and half-pint vessels of different kinds, various types of saws, hundreds of looking glasses, tons of glass beads, brass pans with tops, thousands of needles, thousands of fish hooks, and bars of iron and steel.[7] Gray had particular success having the ship’s blacksmith fashion the iron bars into “chizzels,” short pieces of iron drawn to something of an edge at one end. Copper, for ornamentation, would have found a ready market in some locations, especially near Nootka Sound, but Gray had little on board. There were variations in prices in this trade, as successful bargaining sometimes required greater quantities of trade goods, and sometimes less.

Experience trading on the Northwest Coast would accumulate quickly. In April 1790, an English trader, Archibald Menzies, after returning from the Northwest Coast, submitted to Sir Joseph Banks, one of the leading British proponents of the trade, a sort of shopping list of desirable trade goods. In addition to iron in various shapes and sheets of copper and brass, Menzies recommended sending a variety of iron, tin, and copper or brass tools (especially knives and fish-hooks) and implements. He also suggested that “any Vefsel going there ought to be supplied with two Black Smiths & a Forge together with the necefsary utensils for working Iron, Copper & Brafs into such forms as may best suit the fickle disposition of the Natives.”[8]

Gray returned to Nootka on June 16, 1789, to learn that Kendrick had remained practically inert there. In fairness, the smaller sloop was better adapted than the larger ship to the coastal trade. The two commanders swapped vessels, and Gray left Nootka July 30 in the Ship, Columbia to sell his furs in Canton, while Kendrick remained behind to trade in the Sloop, Lady Washington. Kendrick proved to be something of a renegade. He took control of Lady Washington as though he owned the vessel, eventually re-rigged it as a brigantine, and spent considerable time in the Sandwich Islands trading for sandalwood. Kendrick never left the Pacific. The best evidence is that he died December 12, 1794 at “O. Whahoo” (Oahu), having incurred debts in excess of the value of his ship and cargo.[9]

Nearly two years out of Boston and on the far side of the world, Gray needed rest and resupply on his way to Canton. For these he touched at the Sandwich Islands, arriving there August 24, 1789, and staying 24 days. For American and European ships visiting the Islands, resupply meant buying such foods as vegetables, coconuts, sugar cane, yams, and especially hogs – Gray “bro’t off with me on deck one hundred & fifty live Hogs” – along with necessities like cordage (which Hawai`ians had developed for their own vessels from native plants) and water. In the 1780s this trade, like that on the Northwest Coast, was primarily barter. Copper seemed to have little value in the Islands, but the Hawai`ians did want iron. Many visiting ships’ logs, in describing the trade, noted the effective prices of various items in terms of iron nails. Prices escalated rapidly as increasing numbers of vessels touched there, and some visiting mariners seeking to curry favor with the Hawai`ians traded muskets, powder, and balls for supplies, resulting in a kind of arms race among rival groups in the Islands.[10] This pattern shifted after the conquest of all the Islands except Kaua`i by Kamehameha I, completed in 1795.

Refreshed and resupplied, Gray sailed from the Sandwich Islands to China. Chinese authorities segregated their trading partners into distinct zones. They restricted Russian traders to an overland route by refusing to trade with them anywhere but Kyakhta, a trading post on the frontier between Mongolia and Siberia. Most others came by sea: the Portuguese to Macao, and the Americans and British to Canton (Guangzho). They allowed American and British merchant houses to have agents, or “factors,” residing in a kind of foreign merchants’ ghetto in Canton.

Merchants intermediating trade between Spain and China could purchase goods with silver from the Manila galleons. Not so the Americans, who, like the Russians, mostly brought furs to exchange for Chinese goods.

Unlike the trade on the Northwest Coast or in the Islands, the exchange of goods in China was not barter. Foreign ships had to land (or smuggle) their cargoes of furs, sell them, and use the proceeds to refit, repair, and provision their ships and purchase the Chinese goods that were the objective of the whole enterprise. When Gray arrived at Canton, he carried instructions to deal with the firm of Shaw & Randall, who had arranged with Joseph Barrell, the ship’s owner, to broker the ships’ dealings, steer them through the maze of port charges, import duties, and other fees, and if necessary provide short-term trade financing. Gray’s final account with Shaw & Randall, dated at Canton February 9, 1790, credits Gray 21,400 “Head Dollars”[11] for “Sales of Ship Columbia’s Cargo to Rinqua Security Merchant for said Ship.” On the other side of the account were debits of 1605 dollars for commission on the sale (Shaw & Randall had negotiated the 7½% commission rate with Barrell), 8588.20 for “Bill of disbursements & factory [the business of the factor] expenses, and finally 11,241.51 for “Invoice of Bohea Tea shipped on account & risque of the owners & consigned to Joseph Barrell for balance.” A credit of 4.71 by cash from Capt. Gray balanced the account.[12]

In a letter of the same date, Shaw & Randall express regret that Gray had brought his furs in through regular channels, rather than smuggling them before entering port. As a consequence, Gray not only ended up paying heavy duties and port charges, but he also had to borrow from Shaw & Randall at interest (presumably part of the “factory expenses”), and thus only had sufficient funds to buy the inferior, Bohea tea.[13]

Gray sailed from Canton February 12, 1790. He reached Boston by way of the Cape of Good Hope August 9 of that year. The members of the Barrell syndicate sold the tea for cash and collected freight charges for a cargo Gray had agreed to carry from Canton to Boston for a Sam Parkman. Barrell’s final account for the “Adv[entu]r[e] to the Pacific Ocean” showed that his share of the profit amounted to £416 15s 8d,[14] a return of 21.3% – not a disaster, but probably disappointing for a three-year venture with a high probability of a heavy loss, and no hope of liquidity until their ship came in, if it ever did.

Gray thus became the first American to accomplish a circumnavigation. His route, from Boston to the Northwest Coast by way of Cape Horn, then on to Canton (almost always with one or more stops at the Sandwich Islands), and finally home by way of the Cape of Good Hope, became known as the “Golden Round.” Gray’s voyage was not a large financial success, but Barrell and Gray both felt that the potential of the business was great enough, and that they had learned enough from the voyage, to justify another, which Barrell’s syndicate (with a few changes in membership) also financed. Gray himself took a share in the second “adventure.”

Gray sailed again from Boston on September 28, 1790, after just a few weeks at home. He returned July 26, 1793. Barrell’s investment for 5/14 interest in the “Second Voy[ag]e to Pacific Ocean” was £2233 11s 9d, and his share of the profit was £4959 0s 6d,[15] a return of 222% – a tenfold improvement over the first voyage. Experience contributed to the second venture’s success. With a clearer idea of the best times and places at which to trade for furs, more precise knowledge of the types of trade goods that would yield the richest return in furs, and a better idea of how to navigate the Canton trading system, Gray was able to gather more and better furs, and translate a larger fraction of their value into tea. Among the trade goods, Gray carried sheets of copper, which were in demand on parts of the Northwest Coast. And to avoid the regrettable error of entering his furs for sale through dutiable channels in Canton, Barrell counseled Gray to “avoid the excessive charges of going up to Canton; and, from the experience we have had, it appears plainly a much higher price may be obtained at the mouth of the river of Canton than in the city; we would therefore advise your selling at the mouth of the river.”[16]

When Gray arrived at Whampoa (outside Canton), his Clerk, John Hoskins, wrote to warn Barrell that prices for furs were poor, and they would probably need to trade at least some of their furs for goods, rather than cash. Hoskins reported, “’tis impossible to say the amount our skins will fetch, but I don't expect they will exceed Forty thousand dollars. this is a small price for our quantity of Furrs, but there are a great many at market and many more expected.”[17]

The Columbia sold 1117 large sea otter skins (they sold 700 “indifferent” skins on the first voyage), plus a quantity of small skins, tails, pieces, and land furs, for very close to the 40,000 dollars Hoskins estimated (three years earlier, they realized just 21,400). Their return cargo included over 175,000 pounds of Bohea tea, small quantities of Hyson and Souchong teas, sugar, a large quantity of various types of Chinaware, and nankeens, booked at a total value of 33,210.64 dollars.[18] The ship’s accounts translated from dollars to pounds at the rate of 6s to the dollar. (During the years from 1790-1792, the Bank of England paid about 61d, or just over 5s, for dollars,[19] but again, the pounds in Barrell’s books were not necessarily pounds sterling). In the final analysis, the voyage took approximately £1500 worth of trade goods, exchanged them for furs, which they sold in Canton for about £12,000, the proceeds from which (after deductions for expenses, charges, provisions, and repairs) they used to buy tea and other goods that the concern was able to sell in Boston for a bit more than £20,000.[20]

During his second voyage, on May 11, 1792, Gray entered the mouth of the Columbia River, which he named for his ship. Previous explorers, including Bruno Hazeta during a 1775 Spanish expedition, had noted an opening at the right latitude, and sketchy tales of a great River of the West went back hundreds of years. Still, as late as the month before Gray entered the River, the English navigator George Vancouver had taken note of the change in the color of the water outside the Columbia’s mouth but dismissed it as being of little importance. Still, it hardly seems fair to say that Gray discovered the river, since as soon as he came to anchor, they engaged in an energetic trade for furs and salmon with the people there.

The Northwest Coast fur trade would continue to attract New Englanders for another couple of decades, but as overhunting depleted the North Pacific sea otters and changing fashions in China weakened the market for furs, the Yankee traders turned their attention to other opportunities. By the 1830s they were coming to California for cattle hides and tallow. But that is a story for another day.

[1] Robert Gray to Joseph Barrell Esq’r & Company, Canton, Decem’r 17th 1789, Columbia Papers (bound volume of photocopies), MS N-1017, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston

[2] McCusker, John J. and Russell R. Menard, The Economy of British America, 1607-1789 (Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture by the University of North Carolina Press), 1985.

[3] The best comprehensive study of the Northwest Coast fur trade is James R. Gibson, Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press) 1992.

[4] Joseph Barrell to Sam’l B. Webb Esqr, with salutation “Dear Sam,” Boston, 17 July 1787, Columbia Rediviva collection, Mss957_B1F1_002, The Oregon Historical Society, https://digitalcollections.ohs.org/letter-from-joseph-barrell-to-samuel-webb-2

[5] Barrell & Company, Barrell & Company Account Books, 1770-1803 (inclusive), Vol. 3, Ledger, 1784-1802, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Boston, p.112 https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/11/archival_objects/2785717 Barrell kept his books in pounds, shillings, and pence into the 19th Century. These were not pounds Sterling, however. In 1784, the Massachusetts legislature enacted a statute making foreign gold coins legal tender at £5 6s 8d per ounce [Joseph B. Felt, Historical account of Massachusetts currency, Burt Franklin research & source works series #223, 1968, p. 200]. In England, the average price of gold in bars in 1784 was £3 17s 11¼d [Average Prices of Gold in Bars from 1710 to 1787 Inclusive, Banks Collection, CO4:91, Feb 8, 1788, Sutro Library, San Francisco State University]. Accordingly, the Massachusetts pound was worth a bit less than 75% of a pound (15s) Sterling.

[6] Details of this voyage are from Frederic W. Howay, Ed., Voyages of the “Columbia” to the Northwest Coast 1787-1790 and 1790-1793 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society) 1941

[7] Mary Barrell, Boston accounts and cargo lists, 1787-1790, Columbia Rediviva collection, Mss957_B1F5, Oregon Historical Society, https://digitalcollections.ohs.org/boston-accounts-and-cargo-lists

[8] Archibald Menzies to Sir Joseph [Banks], Joseph Banks Collection, Sutro Library (California State Library, San Francisco State University), PN 1:17, April 4th, 1790

[9] John Howel to Joseph Barrell and others, Canton, 11 May, 1795, transcribed in Howay, Ed., Voyages of the Columbia. Howel took on the winding-up of Kendrick’s business after his death.

[10] For example, “ARGONAUT: Log and journal kept by James Colnett,” 1789 Apr 26 – 1791 Nov 3, ADM 55/142, UK National Archives, Kew

[11] “Head dollars” were an artefact of both the Manila galleons and the ascendancy of the East India Company. Spanish New World silver, minted into coins of one Spanish dollar or 8 riales (whence “Pieces of Eight”) and brought by way of Manila, were in heavy use in the China trade. As Gray’s account shows, they also came into use as unit of account. Chinese merchants often marked these coins with their “chop,” certifying their weight and value. In similar fashion, the East India Company stamped the image of the King’s head on Spanish dollars, making them “Head

dollars.” From 1811, the Bank of England sought to supersede the practice by issuing “Bank of England dollars” for the same purpose and market. These were technically tokens, rather than coins, because they were not legal tender British money.

[12] “Captain Robert Gray & Richard Hoare for owners of Ship Columbia in Account with Shaw & Randall,” ), dated Canton, February 7th 1790, Columbia Papers (bound volume of photocopies, MS N-1017, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston

[13] Shaw & Randall to Joseph Barrell, Esqr, Canton, February 7th 1790, Columbia Papers, Mass. Hist. Soc.

[14] Barrell & Co. Account Books, 1770-1803 (inclusive), Vol. 3, p. 112

[15] Barrell & Co. Account Books, 1770-1803 (inclusive), Vol. 3, p. 137

[16] Joseph Barrell to Robert Gray, Boston, September 25, 1790, transcribed in Howay, Ed., Voyages of the “Columbia” to the Northwest Coast

[17] John Hoskins and Robert Gray to Joseph Barrell, Ship Columbia Whampoa, 22 Decr. 1792, transcribed in Howay, Voyages

[18] George Barrell’s Journal, 1806, Tho. Davis Journal, 1806, and Ship Columbia papers, 1787-1793, Columbia Rediviva collection, Mss957_B1F11, Oregon Historical Society, https://digitalcollections.ohs.org/george-barrells-journal-1806-tho-davis-journal-1806-and-ship-columbia-papers-1787-1793

[19] Prices at which the Bank bought Dollars in the following years, undated table for the years 1757-1797, Banks Collection, CO1:62, 1798, Sutro Library, San Francisco State University

[20] Trade goods value: Calculated from cargo list in account, Ship Columbia for Outfitt and Cargo, undated, Columbia Papers (bound volume of photocopies, MS N-1017, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston; Value of furs and value of cargo for Boston at Canton: see previous footnote; Proceeds at Boston: Barrell & Co. Account Books, 1770-1803 (inclusive), Vol. 3, p. 137 gives Barrell’s share of cash proceeds as £7192 12s 3d. Barrell’s interest was 5/14, giving total proceeds of about £20,139 6s.