Artificial intelligence. Will it drive an explosion in the productivity of labor? Take all our jobs? Lead to the post-apocalyptic world of the Terminator movies? We’ve heard all those possibilities. All are speculative, and like most such speculations will doubtless prove exaggerated. But artificial intelligence is beginning to enter our lives, so it’s worth taking a thoughtful look at what it might and might not be able to do.

I’ll proceed on the assumption that useful forms of artificial intelligence are on the near horizon, and I’ll restrict my attention to their use as productivity tools for writing, form-filling, and decision-making in response to well-defined problems. The influence of artificial intelligence on such work is likely to be analagous to the influence of photography on the art of portraiture.

The advent of photography in the mid-nineteenth century greatly expanded the reach of portraiture. Many subjects who could never have sat for an artist’s portrait could spare the time for a photographic one. Consider this example from the Civil War:

We don’t know why this particular family sat for this portrait, or whether they or the photographer paid for it. The expressions on their faces are stony, likely owing to the need to sit motionless for a long exposure. But it illustrates how the new technology expanded portraiture to a broader market, just as artificial intelligence may expand the availability of competent writing. Without photography (in this case by the early ambrotype process) we probably wouldn’t have any portrait of this Union soldier and his family. Photography increased the number of people capable of producing interesting images, expanding the availability and reducing the cost of portraitists’ services.

We know from our own experience that photographers vary in skill — some have a keener eye than others, some a more artistic sense of composition, some greater command of the technical aspects of the art. So it is likely to be with AI-based work. Some people will simply be better than others at using the new tools. Some practitioners will use them to develop new techniques and capabilities, improving the range and quality of work product available.

Since the advent of digitial photography, and especially since the rise of smartphones equipped with excellent cameras, amateur portraiture, from selfies on up, has become so easy and commonplace that we don’t even think about it. Put another way, ordinary portraits have become ubitiquous and virtually free. AI may produce an analagous phenomenon. In a way, it already has: first-year college students can use ChatGPT or a similar app to produce Wikipedia-level papers on standard undergraduate topics with minimal effort. The trouble is that they’re likely all to write more or less the same paper. Ordinary writing, like ordinary portraiture, is on its way to becoming ubiquitous and free.

If AI, like photography, makes average work better but lowers its value, it should also elevate the exceptional.

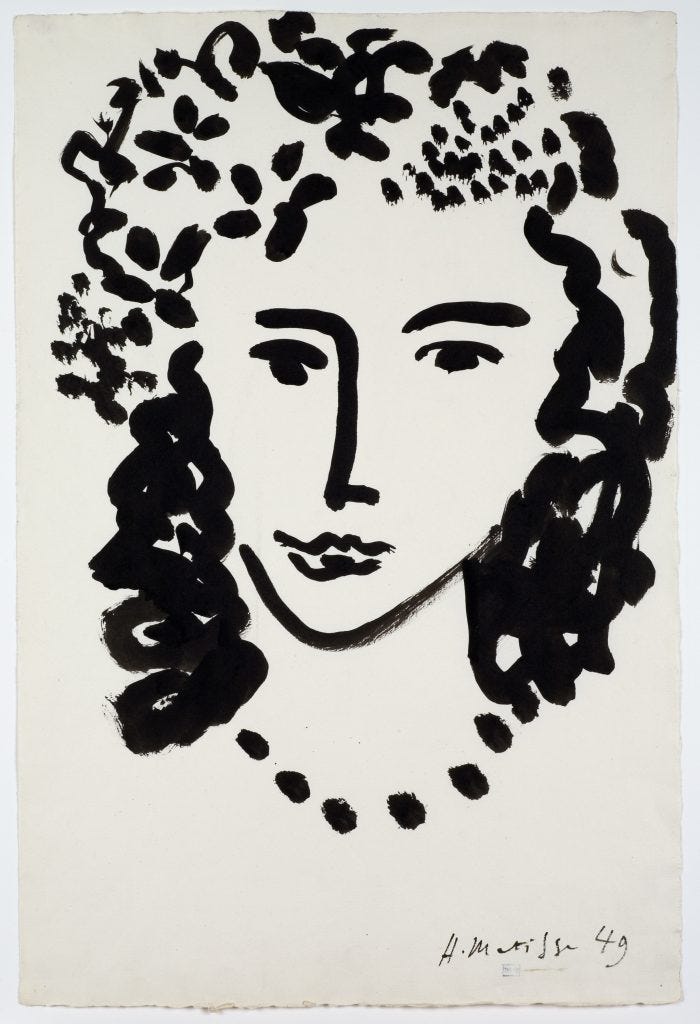

Henri Matisse, Large Head, ink on paper, 1949.

Consider this drawing by Henri Matisse. At first glance, it depicts an interesting face in a pleasing way. But this is no cellphone selfie. On a closer, longer look it becomes an entire conversation among the artist, the subject, and the viewer. It raises all sorts of questions: Who is she? The usual supposition is that she is Monique Bourgeois, a nurse who later became Sister Jacques-Marie and inspired the artist’s last major project, stained-glass windows for a new chapel in her convent in Vence, France. Or, it could be a different friend, Nadia Sednaoui. If the subject was either of those two women, she was not just a model paid to sit for a portrait.

We know that by the time of the drawing Matisse was quite ill. What was his relationship with the subject — friend? nurse? companion? lover, former or current? All four? The portrait also invites us to wonder what she is thinking. A few simple strokes give her expressive eyes — I see someone mostly calm and at peace, with some sadness underneath. But her mouth is not quite fully calm, even if she doesn’t seem about to speak. How about her hair? My spouse thinks Matisse was drawing a hat; I think he has whimsically turned her hair into birds. Regardless, the artist was not merely drawing a likeness of a face. He created an extra dimension by giving us his view (or what he wanted us to see of his view) of a woman with a life, a history, and some kind of relationship with him.

Can the best photography accomplish what Matisse has with his drawing? Yes, but only the best. Similarly, skillful hands will likely use AI technologies to produce exceptional creations that would otherwise be impossible.

AI may allow us all to become Wikipedia, but only a few will be able to use it to become Matisse. At its worst, this could create a societal danger different from the Sorcerer’s Apprentice or Terminator fears that receive more attention. If artificial intelligence displaces significant numbers of workers performing routine tasks while enhancing opportunities for high-skilled workers, it could exacerbate the skewness of income distribution across the workforce. If such a shift became a long-term trend, the resulting social tensions could be severe.

Artificial intelligence appears likely to improve productivity by automating a broad range of routine tasks and increasing their uniformity. If the development of photography provides a reasonable analogy, then the dullness of its output in ordinary applications will highlight the value of the exceptional, from creators able to introduce dimensions into their work that AI cannot reach on its own.